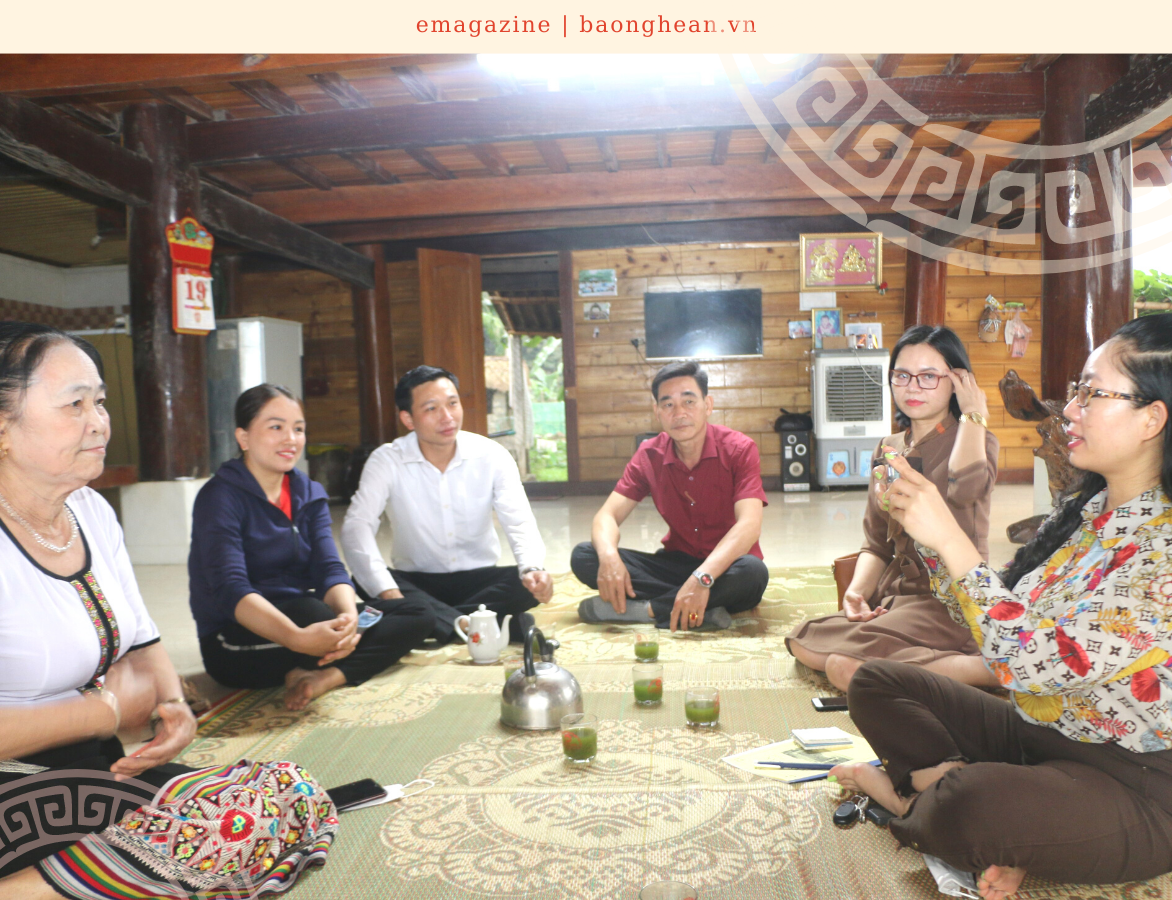

Chau Cuong commune, Quy Hop district, is home to two ethnic groups living together harmoniously: the Kinh and the Thai (comprising two subgroups: Tay Muong and Tay Thanh). According to the Chairman of the Chau Cuong Commune People's Committee, Sam Phuc Thao, many beautiful cultural traditions are still maintained by the Thai people and incorporated into village customs and regulations. For example, in the past, marriages among the Thai people were arranged by parents, with the custom of exchanging gifts as a token of trust (called "hong lan"). Once the "hong lan" was exchanged, the son would bring the gifts home to his parents and set a wedding date. For the couple to become husband and wife, a representative from the groom's family would visit the bride's family to present the gifts as a token of trust and inform the family. If the bride's family agreed, the ceremony was considered successful. After the proposal and the bride's family's consent, the groom's family would visit the bride's family every few months (the visit must coincide with the proposal day). This custom aimed to strengthen and solidify the bond between the two families. At the same time, the son is required to live with the bride's family (for 10-15 days) until the wedding day. "This is the most challenging period, because the young man is not allowed to eat meals at the same table with his wife's parents, sister-in-law, and other female relatives, and must sleep separately. On the wedding day, the groom's family usually picks up the bride in the middle of the night or early morning," Mr. Thao added.

Currently, the custom of exchanging gifts as a token of trust (hóng lánh) still exists, but some places have eliminated some cumbersome rituals such as the groom living with the bride's family or welcoming the bride at midnight… and the village regulations and customs clearly state the encouragement of organizing wedding ceremonies according to the new way of life.

For example, the custom of wife abduction originated from couples whose parents did not approve, leading them to abduct a wife. Before abducting, the young man would often leave something on the girl's family altar to signal to her family that he had taken their daughter. The next day, the young man's family would bring gifts to atone for their sins and ask for her hand in marriage. This custom later transformed and became a harmful practice, which the Thai people call "wife abduction." Later, the custom of wife abduction was modified and included as a prohibition in village regulations to suit contemporary life.

“Besides the collective will and unity of the community, the village regulations and conventions are adjusted to meet the requirements of Resolution No. 5, 3rd Congress of the Central Committee of the Communist Party of Vietnam on building and developing Vietnamese culture and people, meeting the requirements of sustainable national development, and Resolution 05-NQ/TU, dated December 14, 2016, of the Provincial Party Committee on building cultured people and cultured families in Nghe An to meet the requirements of integration and development,” – the Chairman of the People's Committee of Chau Cuong commune emphasized.

According to Mr. Thai Tam, a researcher on the Thai ethnic group in Quy Hop district, the customs and traditions of the Thai people in areas such as Quy Hop, Nghia Dan, Que Phong, Con Cuong, Tuong Duong, and Ky Son mostly retain the essence of traditions from thousands of years ago. These traditions are deeply rooted throughout history. Currently, many customs have been improved and supplemented in village regulations and customs, but the main customs are still maintained in the lives of the Thai people. For example, in Ky Son and Tuong Duong districts, in many families and clans, while the custom of the groom living with the bride's family and demanding a dowry is still maintained, it is no longer as strict as before. The dowry demand now carries only spiritual significance, not the heavy material burden it once did. Regarding funerals, in the past, when a family member passed away, the son-in-law would place the body in a coffin. After the body had been kept at home for three days and nights, the family would invite a shaman. On the third day, precisely at the time the buffaloes come out of the forest to graze in the fields, stream banks, and ravines (around 2-3 pm), the body is prepared for burial. Currently, according to the new village regulations, the practice of waiting three days before burying the deceased has almost completely disappeared.

“In the past, some Thai villages and clans had a custom of selecting daughters-in-law and sons-in-law for ancestral worship, called the ‘liep quai’ ceremony, during funerals (the number of daughters-in-law and sons-in-law depended on the deceased's position). Some funerals selected up to 10 pairs of daughters-in-law and sons-in-law to perform this ritual. These pairs would walk around a buffalo; in every funeral, the family had to slaughter one buffalo for the funeral ceremony. When the ceremony ended, the buffalo was butchered, but the buffalo's head was kept and brought to the grave the next day to be offered to the deceased right on the tomb. However, according to new regulations and amendments to the village customs and traditions, many places have omitted these cumbersome rituals,” Mr. Thai Tam said.

The Thai people have always been very conscious of creating and preserving their ethnic identity. In many places, the preservation of traditional crafts (brocade weaving, embroidery, etc.) is recorded in village regulations and customs, and is developed and passed down through generations by Thai women, creating goods for exchange and increasing income while also preserving traditional clothing.

Furthermore, the Thai ethnic group is also very concerned with preserving and safeguarding its rich and unique cultural and artistic heritage, such as the monumental epic Lai Khun Chuong, the long narrative poems "Lai Long Muong," "Lai Noc Yeng," "Lai Et Khay," folk songs like Nhuon, Suoi, Lam, Khap, etc., and musical instruments such as the khene, flute, gongs, drums, etc. Currently, the regulations and customs of many Thai villages clearly define the responsibilities of each citizen and each family in preserving the cultural values of the ethnic group. For example, in Muong Ham village, Chau Cuong commune, Quy Hop district, where 123 Thai households and 3 Kinh households live, the village's regulations are based on preserving and promoting the customs and traditions of the homeland, upholding the good standards and practices of the ethnic group, eliminating outdated customs, and developing healthy forms of cultural activities. The village's regulations also clearly state the establishment of an amateur performing arts group to participate in the annual Muong Ham traditional cultural festival. Accordingly, the folk song club of the Thai ethnic people here was established very early (in 2002) and now has 80 members of all ages, led by Folk Artist Luong Thi Phien. In addition to participating in festivals and cultural activities, the club focuses on teaching Thai folk songs and traditional musical instruments to children in and outside the village, especially during the summer holidays.