Recreating the world's first sound recording hidden in a Thomas Edison doll

Scientists have found a way to listen to recordings in a phonograph hidden in a "talking" doll made by Thomas Edison using new technology, using a microscope to photograph the grooves in the recording and recreate the sound on a computer.

Robin and Joan Rolfs own two rare dolls, made by Thomas Edison's record company, but they don't play records on the phonographs hidden inside them.

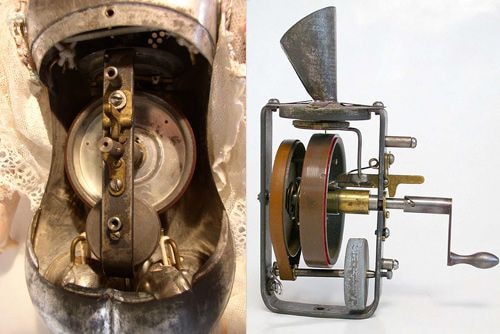

In 1890, Edison came up with a way to miniaturize a record player and put it inside a doll. The doll had a handle on its back, and to listen to music, one had to turn it. This invention was a failure, children thought the toy was difficult to control, and made creepy sounds.

The Rolfs knew that if they risked turning the handle, they would most likely damage or destroy the grooves inside the record player, which consisted of many round cylinders. So, for many years, no one heard the mysterious sound inside the doll.

However, audio researchers say the recordings hidden in the dolls are of historical value. They were the world's first entertainment recordings, and the young women hired to sing them were the world's first studio artists.

So for years, the Rolfs have been trying to figure out how to listen to the recordings. Experts at a US government laboratory have come up with a way to listen to the precious recordings, without touching them.

|

| Miniature CD player hidden inside doll. Photo: Science 20 |

This technique uses a microscope to create detailed images of the grooves on a record player. A highly accurate computer then simulates the sound by creating a sound map through a needle inserted through those grooves.

In 2014, this technology was first introduced to the public.

“We were very concerned about damaging these recordings,” said Jerry Fabris, curator of the Thomas Edison Museum in West Orange, New Jersey.

The technology, called Irene, involves a complex process of image acquisition, sound reconstruction, and noise removal. Developed by physicist Carl Haber and engineer Earl Cornell at the Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory, Irene can extract sound from grooves and records, and can also reconstruct sound from badly damaged, inaudible recordings.

“Now we are hearing sounds of history that I never thought I would hear,” Mr. Fabris said.

Irene technology uses a microscope mounted on a rod to capture thousands of high-resolution images of the groove details. The images are then combined to create a topographic map of the cylindrical groove surface with varying heights, with a thickness as small as 1/500th of a human hair. Pitch, volume, timbre, and tempo of the music are all encoded on this surface.

The sound waves were digitized on a computer, then filtered for noise, and the rhythm was clearer. The recording from one of Mr. Rolfs's dolls, "There was a little girl," was about 20 seconds long.

“That moment was amazing,” Mr. Rolfs said happily.

Last month, the Thomas Edison Museum released three recordings of Edison's dolls online, including those from two of the Rolfs' dolls. "There are probably more, and we hope to digitize them," Fabris said. "Now we have the technology to listen to the recordings without damaging them."

According to VnExpress