The power of the Electoral College in US elections

Electors cannot be members of Congress or hold federal office. States decide on other criteria for selecting electors.

In US history, there have been five times when the elected president received fewer popular votes than the defeated, most recently the case of Donald Trump in the 2016 election.

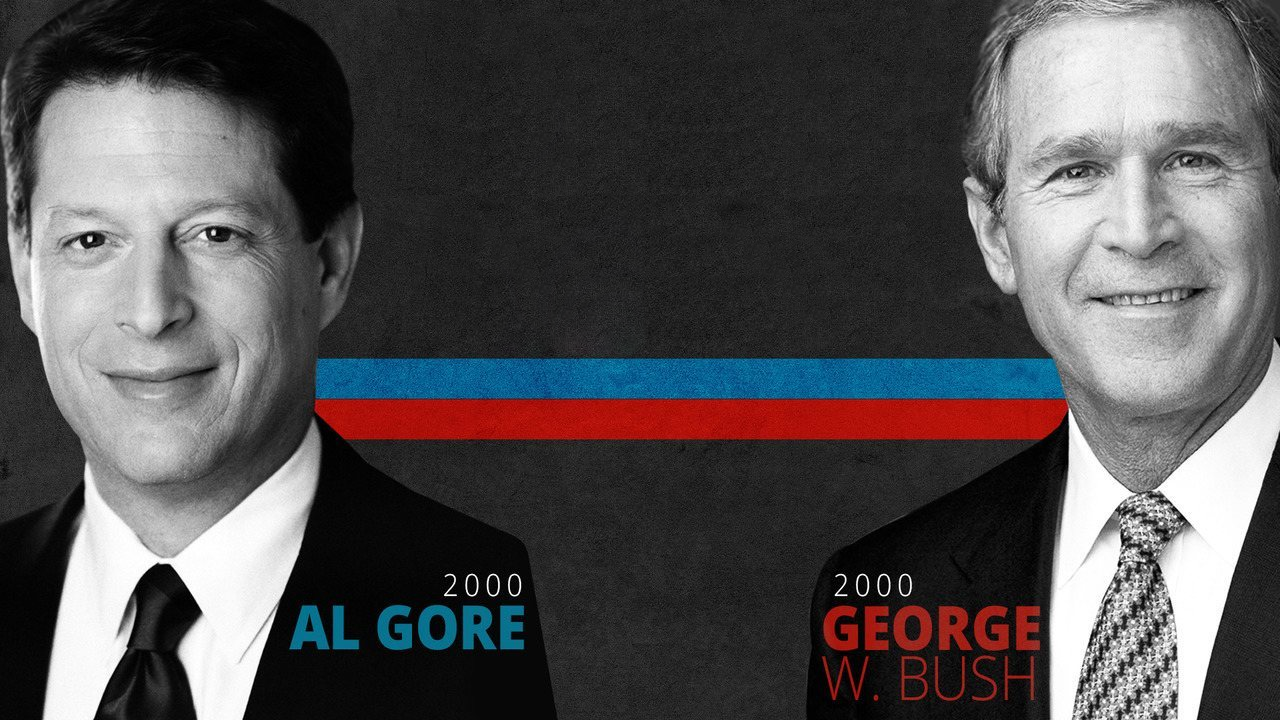

The United States entered the 21st century with a historic presidential election. The 2000 contest between Republican George W. Bush and Democrat Albert Arnold Gore Jr. is considered one of the most important in recent decades, highlighting the complexities involved in how the Electoral College vote outweighs the popular vote.

George W. Bush's victory was decided by the Supreme Court, which awarded him 537 more popular votes in Florida and all 25 electoral votes in the state, giving him a final victory of 271 electoral votes and the presidency. Bush won despite losing 500,000 popular votes nationwide to his opponent, Al Gore.

despite losing to his opponent Al Gore by 500,000 popular votes nationwide

It wasn't the first time such a situation had happened and it probably wouldn't be the last.

In US history, there have been 5 times when the winner of the presidential election had fewer popular votes than the loser, the most recent being the 2016 election, when Democratic candidate Hillary Clinton had nearly 3 million more popular votes than Republican candidate Donald Trump but still lost the election because she lost the electoral votes. This number of nearly 3 million popular votes is also the largest margin ever for a losing candidate.

Delegates to the Constitutional Convention of 1787 argued about many things, and one of their biggest disagreements was how Americans should elect their president.

Some of the founders believed that a direct national election would be the most democratic method. Others believed that a direct popular vote would be unfair, because it would give too much power to the larger, more populous states. They also worried that public opinion could be too easily manipulated.

The result of this controversy was the Electoral College, a system in which the American people vote not directly for president and vice president, but for a smaller group called electors. These electors then vote directly for president and vice president, at a meeting held a few weeks after the election.

The Founding Fathers saw this as a compromise between direct presidential election by popular vote and a vote by members of Congress for the president – a form considered undemocratic.

There are a total of 538 electors, including one elector for each U.S. senator and representative, and three electors representing the District of Columbia (Washington, DC). Presidential candidates need at least 270 electoral votes to win the White House. In most elections, the winner of the Electoral College also wins the national popular vote. However, there are exceptions.

The US Constitution stipulates that electors cannot be members of Congress or hold federal office. States decide other criteria for selecting electors. Under the 14th Amendment, ratified after the Civil War, electors also cannot be anyone who has engaged in insurrection or rebellion against the US, or given aid to its enemies.

According to the Constitution, each state has a number of electors equal to the total number of representatives and senators it has in Congress. State legislatures are responsible for choosing electors, but the way they do this varies from state to state. Until the mid-1800s, it was common for many state legislatures to appoint electors, while other states let their citizens decide on electors.

Today, the most common method of selecting electors is by state party conventions. Each political party's state convention nominates a slate of electors, and a vote is held at the convention. In some smaller states, electors are selected by a vote of the state party's central committee.

Either way, political parties typically select people they want to “reward” for their service and support to the party. Electors can be elected officials or state party leaders, or people who have some personal or business relationship with the party’s presidential candidate.

The problem with the Electoral College system is that a candidate can win more popular votes than his opponent nationwide, but still lose the election. This happens when the candidate wins big in populous states but loses narrowly in battleground states and ultimately loses the electoral college.

This is also the factor that shapes the way presidential candidates campaign politically.

In a recent article in the New York Times, Jesse Wegman explained: “Today, 48 states are winner-take-all. As a result, most states that traditionally favor one party or the other are considered safe. No matter how hard the underdog campaigns, that doesn’t change. The states that matter to either party are the battleground states, especially the larger ones like Florida or Pennsylvania, where a difference of a few thousand or even a few hundred votes can flip an entire electoral college from one candidate to the other.”

As a result, campaigns focus on issues that matter in battleground states, like shale oil in Pennsylvania or prescription drugs in Florida. Issues like climate change in California and traffic problems in New York are conveniently ignored.

Another source of dissatisfaction with the Electoral College system is defection by electors – people who vote for a candidate other than the one they pledged to. This happened in the 2016 election when electors broke ranks and did not vote for Mr. Trump.

Between 1796 and 2016, about 180 electors did not vote for the presidential or vice presidential candidate who won the popular vote in their state. However, in U.S. history, these delinquent electors have never been the deciding factor in the outcome of a presidential election.

In the late 1960s and 1970s, polls showed that 65–80% of voters favored abolishing the Electoral College and moving to electing the president by popular vote.

In 1969, the US House of Representatives overwhelmingly approved a constitutional amendment to abolish the Electoral College. However, after a decade of intense debate, the bill ultimately failed in the Senate, despite receiving 51 out of 100 votes in favor. To pass an amendment, it requires the support of two-thirds of the Senate members, or 67 votes.

According to Alex Keyssar, historian and professor of History and Social Policy at Harvard University, in the first decade of the 21st century, support for abolishing the Electoral College hovered just above 60%, including the majority of Democrats and Republicans. However, after the 2016 election, Gallup polls showed that support for the Electoral College increased. The polling company explained: “After the 2016 election, the percentage of Republicans who wanted to replace the Electoral College with a popular vote dropped significantly.”

The issues of the Electoral College are likely to be controversial again in this year's election as the US continues to face the Covid-19 pandemic and the number of mail-in ballots rises to a historic high.

In a New York Times article, political reporter Shane Goldmacher said: “The confusion of rules and deadlines for receiving mail-in ballots from states, including in battlegrounds like Pennsylvania and Wisconsin, all of those factors make it certain that it will be difficult to determine a clear winner in a tight race on November 3.”

He believes the public and politicians should reduce expectations about when the 2020 election will have a clear result.

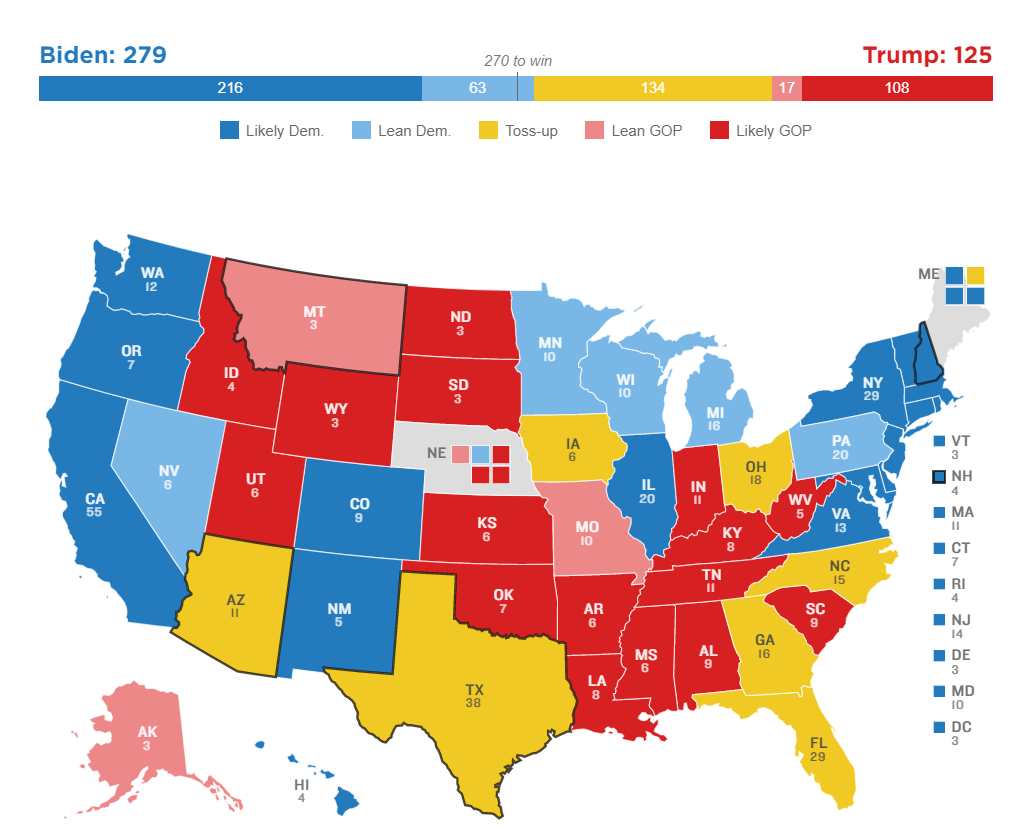

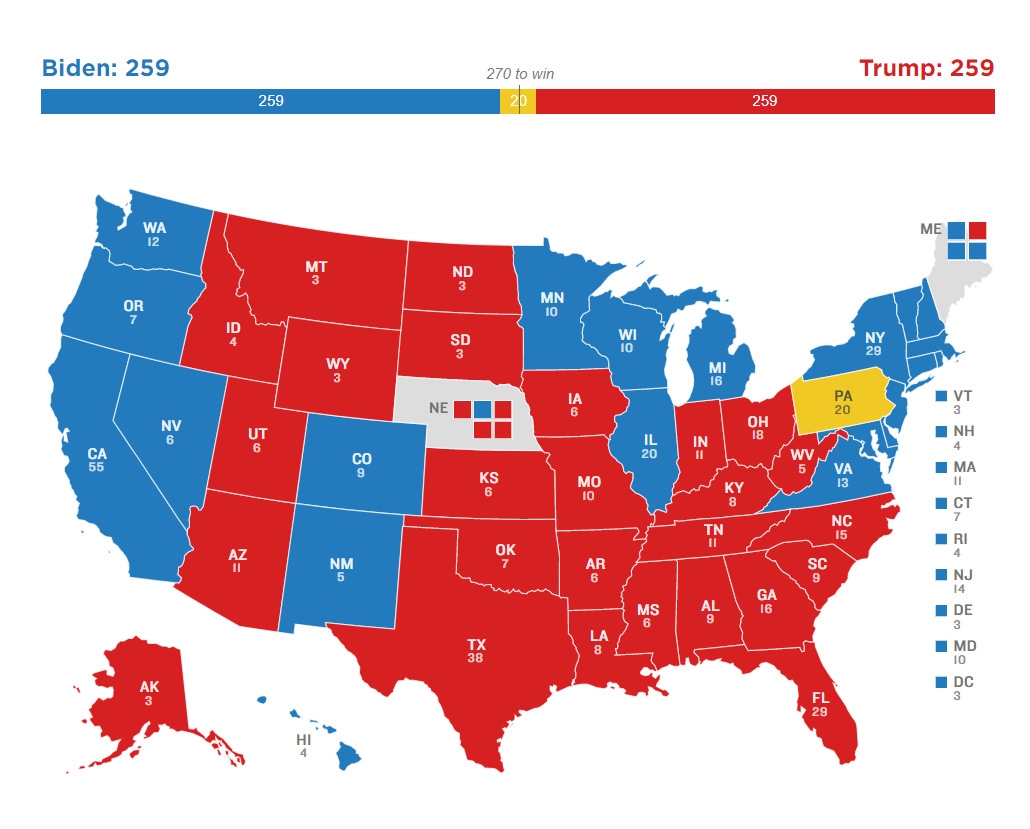

NPR's analysis of the electoral college map in the run-up to the election shows Democratic candidate Joe Biden holding a clear advantage, while President Trump's path is narrow but not impossible given the unpredictable situations in the swing states.

Among states that are likely or likely to favor a particular candidate, Biden leads by 279 electoral votes to Trump’s 125. A candidate needs 270 electoral votes to win the presidency. That means even if Trump wins all the swing states, he still lacks 11 electoral votes and would need to win at least one state that is currently leaning toward Biden. President Trump’s campaign is eyeing Pennsylvania.

This October, NPR moved Arizona from leaning Democratic to swing; Texas — after much hesitation — from leaning Republican to swing; Montana from firmly Republican to likely Republican; and New Hampshire from firmly Democratic to leaning Democratic.

Mr Trump faced a similar predicament in 2016, although if he wins this time it will represent even larger polling errors than were recorded in key states four years ago.

While the math is tough for Mr. Trump, it’s not all bad news. His lead is within the margin of error in polls in all seven battleground states and one swing congressional district in Maine. (Unlike every other state, Nebraska and Maine don’t use winner-take-all rules, but instead allocate their electoral votes through a combination of statewide and congressional district votes.)

In Texas and Ohio, Trump currently leads Biden in polling averages. In other places—Georgia, Iowa, Florida, North Carolina, Arizona and Maine's 2nd congressional district—Biden leads by an average of about 3 percentage points or less.

If all of these areas were to go against Mr. Trump, and if all of the Biden-leaning states except Pennsylvania were to stay with the former Vice President, the electoral college map would be 259-259.

That would leave Pennsylvania as the deciding state, a state that could take longer to count this year because it doesn’t typically process the volume of mail-in ballots it does this year. That could lead to a scenario where the outcome of the election isn’t clear on election night.