The barren lands, with more sedge than the average person; the long sandy beaches where only casuarina trees can thrive; the saline, acid sulfate fields that used to be “dead lands”… but through the hands and minds of the people of Nghe An, they have gradually revived, covered with green fruit trees, turning into billion-dollar shrimp farms, creating valuable agricultural by-products…

Before 2010, Hai Don beach, Bac Thang hamlet, Nghi Tien commune (Nghi Loc) was a long stretch of white sand, where only casuarina trees and sea spinach could grow. Not to mention, there was garbage accumulating in sandbanks and beaches, wasting land resources and polluting the marine environment. Until 2013, Mr. Nguyen Van Hao asked for permission from Nghi Tien commune and then went with his wife to Hai Don sandbank to improve the silver sand, dig holes, fence ponds, and line tarpaulins to raise shrimp...

It is impossible to tell all the difficulties of the early days of transforming the barren sandbank into billion-dollar shrimp ponds. Mr. Nguyen Van Hao said: “All the capital was poured into this sandbank. Building banks, leading water, lining tarps, buying giant tiger prawns and whiteleg shrimp to raise, but because of not mastering the techniques, the shrimp got sick, died, and suffered heavy losses. After a few crops like that, I was able to “filter” experience, master the farming process, so the shrimp lived healthily, reached the set weight, and had a stable output. From there, the family quickly recovered their capital, made a profit, and returned to invest, expanding the farming area.”

From a 1,000m shrimp square2Now Mr. Hao and his wife have expanded the area to 5,000m2.2In addition to raising shrimp in earthen ponds lined with tarpaulin, Mr. Hao gradually switched to raising shrimp in round ponds lined with tarpaulin and roofs, applying high technology to shrimp farming. With an average of 2 shrimp crops per year, the revenue reaches billions, the profit is about 500-700 million VND, Mr. Hao's family has built a house, bought a car, raised children to study, and created regular jobs for 3 local workers.

Initially, only a few households in Nghi Tien commune "risked" going to the sandbanks in Tien Phong and Hai Don to dig ponds and raise shrimp. Now, 11 households have joined with an area of nearly 3 hectares, earning an annual revenue of 15-17 billion VND, creating jobs for dozens of local workers. There are households like Mr. Hao, Mr. Viet, Mr. Cuong... who have become rich thanks to shrimp.

The same is true along the coast of Dien Kim commune (Dien Chau), which was previously abandoned, with long, burning sandbanks, overgrown with weeds and garbage. Since 2010, shrimp farms on sand have been established, creating a prosperous seafood economic zone. High-tech shrimp farms with greenhouses, water fans, aeration systems, running day and night, with stages such as feeding, measuring pond temperature, water environment indicators, etc. all controlled via a smart operating system using smartphones. Thanks to that, each year with 3 "sure" shrimp crops, revenue reaches 2-3 billion VND/ha/year.

According to preliminary statistics, the potential area for shrimp farming on sand in the province is about 600 hectares, up to now over 200 hectares have been put into farming, mainly concentrated in localities such as Dien Chau, Hoang Mai Town, Nghi Loc, Cua Lo Town... Shrimp farming on sand is considered an effective economic model, likened to "turning sand into gold" in Nghe An.

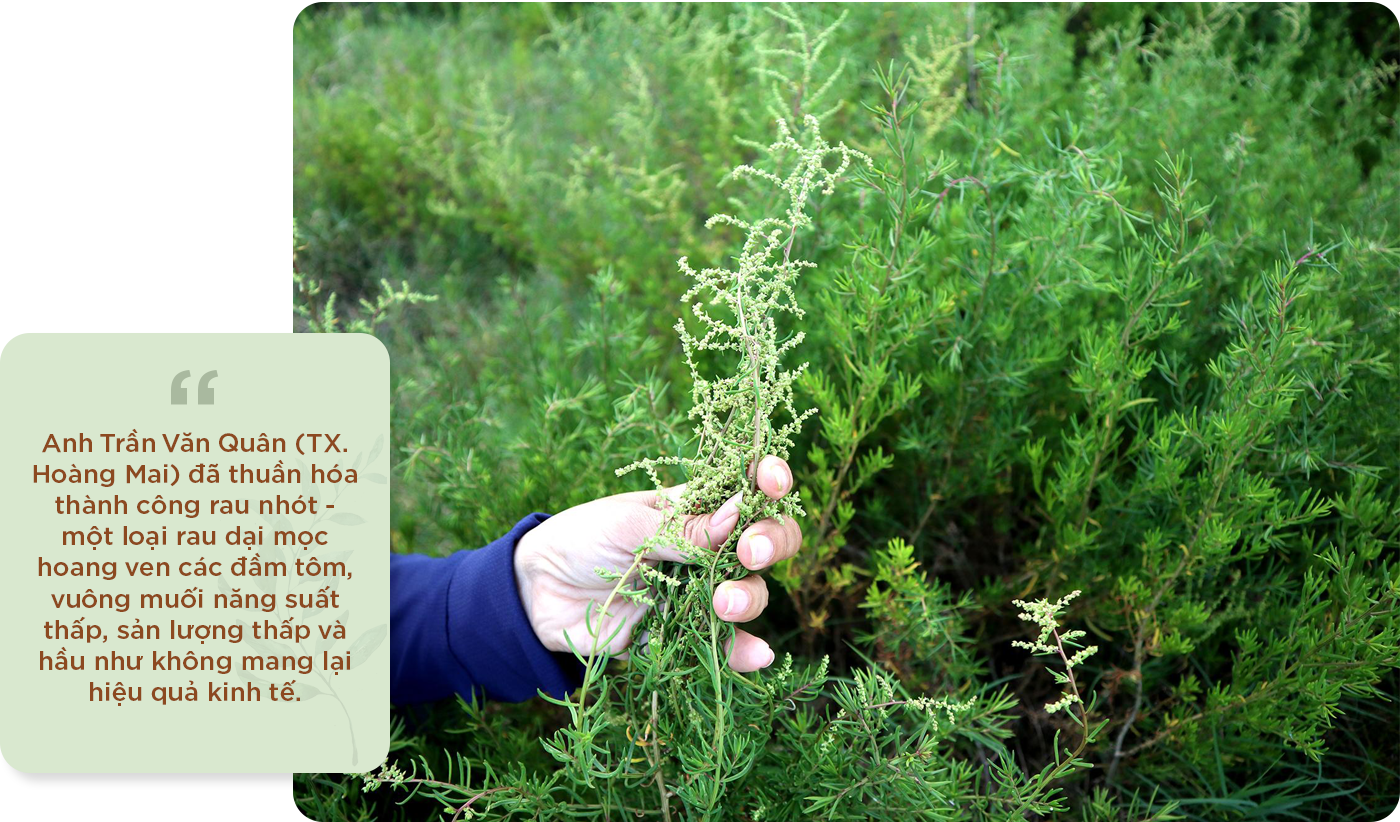

In the scorching summer, when the fields are dry and cracked, the Doi field in Mai Hung ward (Hoang Mai town) is still green with the color of rau loi. Just 2 years ago, this Doi field was still wild, with grass growing higher than the knees, because before that, people had tried to plant beans and peanuts, but the plants were stunted, died young, and had low productivity due to saline soil, so they had to be left uncultivated. Meanwhile, rau loi, a wild plant growing along shrimp ponds and sandbanks along rivers and seas in Quynh Luu, is gradually becoming scarce due to concreting. While market demand is increasing, prices are high, but rau loi is gradually depleted. Worried about the abandoned saline fields and the scarcity of rau loi, Tran Van Quan (born in 1984, in Quynh Vinh, Hoang Mai town) came up with the idea of domesticating rau loi on abandoned saline soil.

After testing the pH level in the soil in Doi field, Mr. Quan found it quite suitable for the water spinach plant. He "took a risk" in subcontracting 1 hectare to turn wild vegetables into commodities to supply to the market in large quantities. "After receiving the contract, I used all my accumulated capital, borrowed from friends and relatives, and invested nearly 1 billion VND in this wasteland to level and improve the soil, build a drainage system and install automatic irrigation nozzles. Water spinach is a wild vegetable, but it is not easy to put it into intensive cultivation. It takes 3-4 times of planting to be successful. On the one hand, we must follow the natural characteristics of the plant, on the other hand, we must know how to add organic substances such as fermented chicken manure, fermented fish sauce residue, and salt water... so that the vegetable plant can grow, develop well, be young and be harvested all year round," said Mr. Quan.

Thanks to those "secrets", Mr. Tran Van Quan has successfully domesticated the water mimosa - a wild vegetable that grows wild along shrimp ponds and salt fields with low productivity, low output and almost no economic efficiency. After domestication, with proper care and process, the water mimosa can be harvested every 3-5 days, each crop weighing 3-5 quintals/sao. Because of the alternating cropping method, Mr. Quan's water mimosa field can be harvested almost every day to sell to the market. The current price of water mimosa ranges from 15,000-25,000 VND/kg; after deducting expenses, each year it brings Mr. Quan's family a revenue of about 1 billion VND, creating regular jobs for 3-5 local workers.

Not only consumed within the province, rau lot is also available in many famous restaurants and hotels nationwide, considered a unique, healthy and clean dish. In particular, many coastal localities in the Central region have contacted Mr. Quan to order seeds, bringing them to experimental planting in saline soil areas.

In the near future, the Nghe An Vegetable Cooperative, owned by Mr. Tran Van Quan, is expected to rent more abandoned saline land, expand the area for growing vegetables and salt-tolerant plants such as sea purslane, ground purslane, sea asparagus, etc. in localities such as Quynh Luu, Hoang Mai Town, Dien Chau; at the same time, cooperate with people in these areas to transfer techniques, plant and consume products with the goal of "greening" saline land, creating livelihoods and improving the environment for people.

“I just hope that when stable growing areas are created, the ingredients of the jute plant will be analyzed and quality tested, and then processed into jute powder, jute tea, jute cake, etc., creating typical products of coastal areas, contributing to the implementation of a sustainable saline agriculture model that adapts to climate change,” said Mr. Tran Van Quan.

(To be continued)