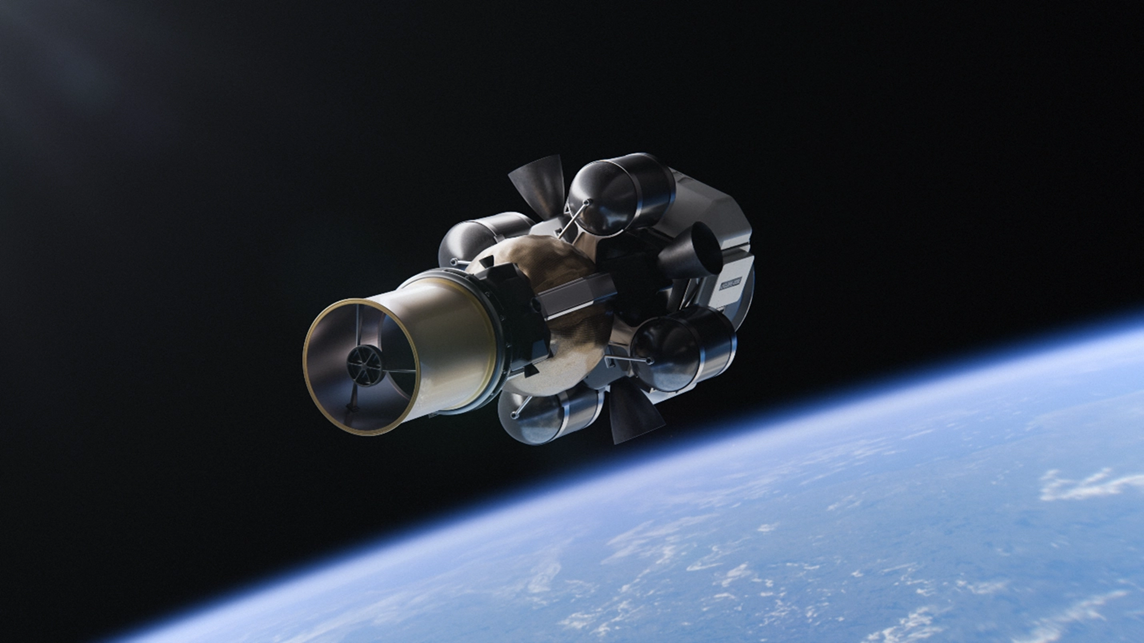

Cyclops, a low-cost American extra-atmospheric interceptor missile.

Long Wall in California introduced the Cyclops extra-atmospheric interceptor system, aiming to reduce costs and increase the number of large-scale defensive munitions.

The increasing frequency of air raids saturated with large numbers of missiles and decoys is causing defense costs to far exceed offensive costs. In this context, the California-based defense technology company Long Wall has introduced the Cyclops extra-atmospheric interceptor system, optimized for low-cost mass production, aiming to fundamentally change the approach to ballistic missile defense.

The cost and "depth of ammunition" problem in defense.

Experience at many hotspots in recent years has revealed a critical flaw in Western missile defense architecture: limited interceptor missiles and very high operating costs. Current systems, while modern and accurate, were developed with a "you get what you pay for" mentality, resulting in consistently low stockpiles.

The adversary exploits this weakness with a large-scale salvo tactic, potentially firing hundreds of ballistic missiles and decoys simultaneously to overwhelm the defense system. Military analysts warn that the offensive missile production capacity of potential adversaries is far exceeding the rate of interceptor missile manufacturing, creating a strategic imbalance.

Long Wall aimed to address that problem directly with Cyclops, focusing on "magazine depth"—the ability to sustain interceptor fire in extended campaigns against continuous attacks. Unlike mid-stage defense systems developed progressively over decades, Cyclops was redesigned from scratch with a "manufactured to fight" mindset.

Breakthrough in extraterrestrial interceptor vehicles.

At the heart of the Cyclops system is the Extra-Atmospheric Missile Controller (EKV). After the booster rocket launches the entire complex into space, the EKV separates, independently searches for, locks onto, and destroys the target during mid-flight, while the ballistic missile is still outside the atmosphere.

The Cyclops's destruction mechanism employs a hit-to-kill principle, using the immense kinetic energy from a high-speed collision to destroy the target, rather than using a fragmentation warhead. This approach allows for the complete destruction of any nuclear or chemical warhead, reducing the risk of toxic substances being released onto the ground.

In the history of interceptor missile development, the electronically controlled warhead (EKV) has always been the most technically challenging aspect and the main reason for the high cost. An effective EKV requires an extremely precise propulsion system to correct its trajectory in a vacuum, along with advanced infrared sensors to distinguish the real warhead from debris and decoys.

Typically, these components are handcrafted to stringent aerospace standards, limiting production. Long Wall says it leverages the latest advances in computing, autonomous systems, optical sensing, and propulsion technology, largely derived from the civilian commercial sector with large-scale production capabilities. The component selection from the outset prioritizes scalability.

Long Wall has now completed the first EKV prototype and begun testing. Thanks to its focus on using components suitable for mass production, Cyclops is expected to achieve a production rate of hundreds, even thousands of missiles per year, instead of just a few dozen like current systems. This helps lower the cost per interceptor and reduces the pressure on commanders to "conserve ammunition," even for low-value or unidentified targets.

Decentralized defense strategy with containerized launch platforms.

Another highlight of Cyclops lies in its deployment architecture. Instead of relying on fixed defensive bases – which are vulnerable to preemptive attacks – Long Wall developed a containerized launch system, placing the entire launch platform and missiles within standard shipping containers.

This configuration allows Cyclops to be transported by civilian trucks, trains, or deployed on the decks of requisitioned cargo ships or small warships without the need for complex infrastructure. Its high mobility and camouflage capabilities make it extremely difficult for the enemy to conduct reconnaissance and plan suppression attacks.

Long Wall also assessed that the cost of the container launcher was low enough to be considered a consumable asset in some scenarios, making commanders willing to accept higher risks to protect strategic targets.

To shorten the integration roadmap, the company is self-funding the initial development phase, using simulators based on the Terminal High Altitude Area Defense (THAAD) system. Relying on simulation data from a proven system increases compatibility with existing command and control (C2) networks of the U.S. and its allies.

Independent flight testing and optimization of production processes.

The flight testing process is one of the factors that makes interceptor missiles very expensive. Long Wall chose to become self-sufficient in this area using an in-house liquid-fueled propulsion system called RSX, which is used for frequent test flights at a low cost.

The RSX is designed for multiple uses: it serves both as a hypersonic flight test vehicle and as a ballistic missile target simulator for Cyclops to practice interception. Thanks to its own test vehicle, Long Wall is not dependent on the expensive and limited test schedules of national test sites, thus shortening the system's completion time.

In terms of manufacturing, Long Wall leverages existing production lines with modular design and commercial equipment such as 3D printing (additive technology), high-precision CNC machining, and in-house electronic assembly. This approach aims to avoid bottlenecks in the supply chain, allowing for rapid increases in production as demand rises.

Potential role in missile defense architecture

Interest in mid-stage interceptor systems is growing as more nations face increasingly sophisticated ballistic missiles and hypersonic weapons designed to penetrate existing defenses. In this context, cost-effective extra-atmospheric interceptor solutions are seen as a necessary direction.

Cyclops still needs to go through many rounds of testing to prove its reliability, cost-effectiveness, and network integration capabilities. However, its introduction marks a shift from expensive, scarce systems to a "high availability, low cost" mindset.

If its objectives are achieved, Cyclops could become a crucial piece in the missile defense architecture of the US and its allies, contributing to restoring strategic balance by making missile interception cheaper and more abundant than before.