Atomic memory stores all the books in the world in a stamp

Dutch scientists have developed a new generation of memory that can store information at individual chlorine atom locations on a copper substrate.

|

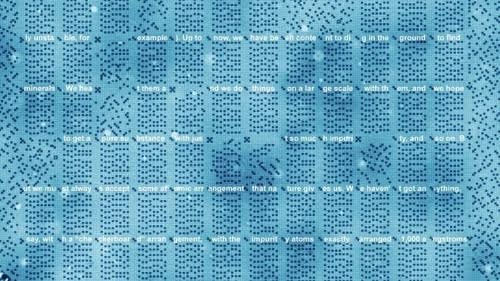

The storage device stores information on individual chlorine atoms. Photo: TU Delft |

According to BBC,This is the work of a research team led by Dr. Sander Otte, Delft University of Technology.

With each bit of data represented by the position of a single chlorine atom, the team achieved a storage density of 500 terabits per square inch (about 6.5 square centimeters), for aThe storage density is two to three times greater than current flash hard drive technology.

“In theory, this density would allow all the books ever written by humans to be stored on a single postage stamp,” Otte said. In other words, the entire contents of the US Library of Congress could be stored on a cube measuring 0.1 mm.

The researchers used a scanning tunneling microscope (STM) with a sharp needle that probes the surface atom by atom. They arranged the atoms in a way that Otte compared to a sliding jigsaw puzzle.

"Each bit of data consists of two positions on the surface of the copper atoms, and each chlorine atom can slide back and forth between these two positions," he said.

"If the chlorine atom is on top, meaning there is a hole below it, we set that bit to 1. Conversely, when the chlorine is on the bottom, above the hole it will be a 0."

Because the chlorine atoms surround each other (except near the holes), they hold each other in place. For this reason, the team believes their method is more stable than using loosely bound atoms, making it more suitable for practical data storage applications.

The team demonstrated this by saving physicist Richard Feynman's famous lecture "There's Plenty of Room at the Bottom" onto a 100-nanometer-wide area.

However, while the future is promising, it is not yet scalable. The storage process requires very low temperatures, minus 196 degrees Celsius, and single-process write and read speeds are still slow, measured in minutes.

In a paper published on the same topic in the journal Nature Nanotechnology on July 18, researcher Steven Erwin of the Naval Research Laboratory in Washington DC also acknowledged these limitations. However,Dr. Otte remains optimistic about the technology.

“With this initial success, we have definitely come a long way,” said Mr. Otte.

“It is important to realize the significance of this achievement – a high-density functional memory device at the atomic scale will at least stimulate our imagination for future milestones,” said Erwin.

According to VNE

| RELATED NEWS |

|---|