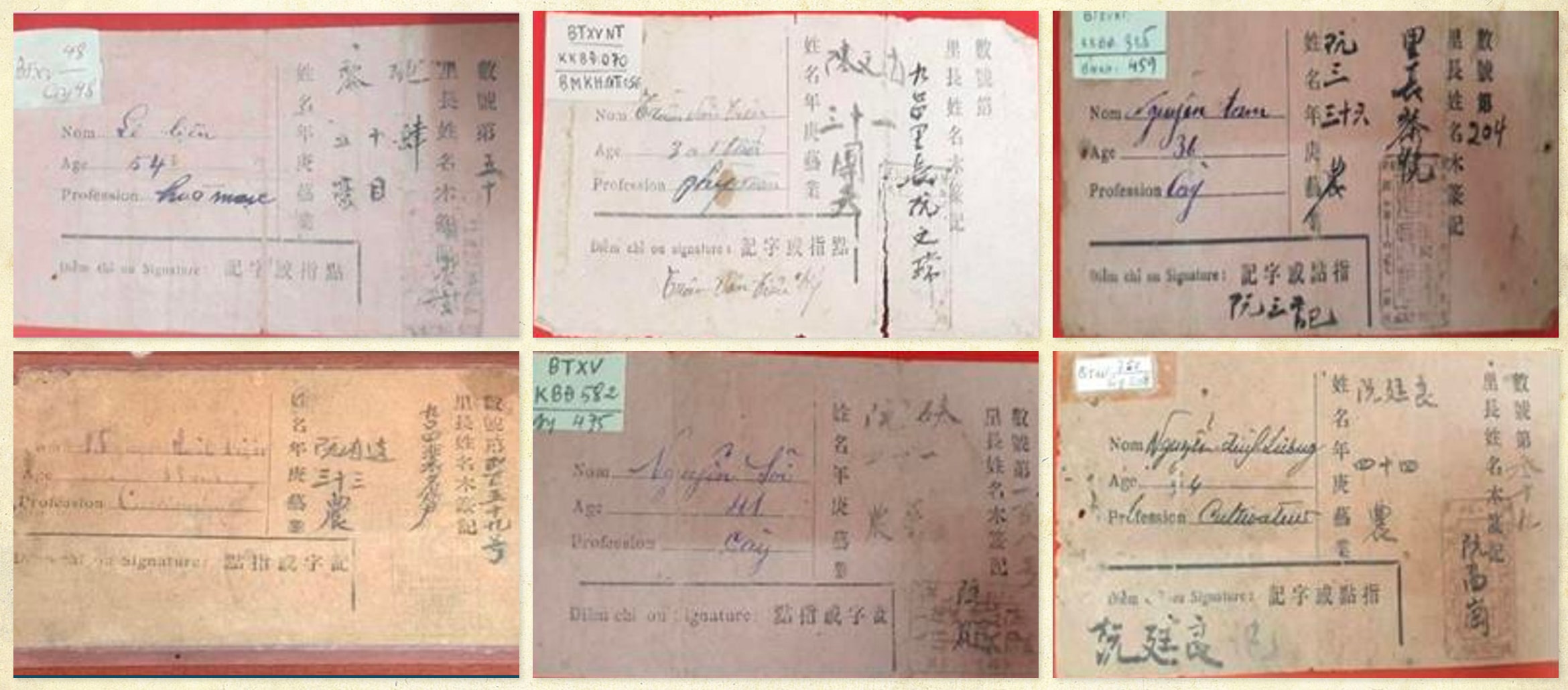

The collection of tax cards is displayed and preserved at the Nghe Tinh Soviet Museum.

The Nghe Tinh Soviet Museum is currently displaying, preserving and promoting the value of many unique collections, especially the collection of pre-1945 personal tax card artifacts.

Poll tax (collection tax, head tax) is one of the types of taxes from the feudal period that was thoroughly exploited by the French colonialists to exploit the Vietnamese people and was the main source of revenue for the state budget, serving the colonial exploitation in Indochina. According to many documents, through each era, the regulations on paying poll tax in Vietnam have been slightly adjusted and have become more specific and detailed.

Under feudalism, most recently the Nguyen Dynasty, the taxes imposed by the Nguyen Dynasty were: land tax, personal tax, corvee tax, mining tax, salt tax, business license tax, and alcohol tax.

“The poll tax is only levied on the inner people (official villagers), who enjoy civic benefits such as being divided public land, being able to participate in government positions in remote areas or outside the commune, and many other benefits. The outer people (illegal or resident) are exempt from the poll tax, but do not enjoy any benefits.(1).

The state relied on the village register to levy taxes and did not collect them directly but distributed them to each village and commune, then the village and commune distributed them to the people. In the register, the population was arranged into many categories: strong, military, civilian, old and disabled with different tax rates. People had their taxes reduced or exempted when there were natural disasters. Tax exempted categories included: people with high positions, children of mandarins in the Nguyen Dynasty, people who passed exams, soldiers, workers, etc.

After the French colonialists invaded Vietnam, the country was divided into three regions with three different governing regimes: Cochinchina, Bac Ky, and Trung Ky. In Trung Ky, the French colonialists kept the feudal administrative system intact to act as an effective assistant to the administrative apparatus and gave them economic and political benefits. The French colonialists made full use of old taxes, increased them sharply, and added many new taxes (in which the poll tax was the main source of revenue), completely changing the nature compared to the feudal period. Western scholar, HL James, commented: "On the rubber back of the Annamese, the State can freely extend the elastic tax rate"(2).

The poll tax was set by the French colonialists and paid annually, levied on people aged 18 to 60. All those subject to poll tax had to have a poll tax card. The card had the signature or fingerprint and seal of the village chief. The card was replaced every year, and the color of the card had to be changed every year. There were different colors of poll tax cards to distinguish between internal and external men and tax-exempt subjects. Men carried the card with them and presented it when necessary. If they were found without the card, they could be arrested. Those who lost their cards and had to pay the tax amount to reissue them. In addition, the French colonialists further narrowed the tax-exempt subjects.

According to the Decree dated June 2, 1897 in the North and the edict dated August 14, 1898 in the Central, the personal tax“skyrocketed from 50 cents to 2.50 dong in the North and from 30 cents to 2.30 dong in the Central, equivalent to the price of 100 kg of rice at that time. The dead were not exempted from tax, the living had to pay instead. The colonial government forced each village to pay the full amount of tax as set.”(3)

In 1908, in the face of heavy oppression and exploitation by French colonialists, a spontaneous, public anti-tax movement of farmers broke out throughout the provinces of South Central Vietnam, but due to lack of leadership and tight organization, the movement was suppressed and eventually disintegrated. After this event, they had to reduce the poll tax from 2.40 dong to 2.20 dong, reduce 4 public service days to 3 days and declare not to increase the 5% land tax.

Since 1919, the colonial government ordered the abolition of tax payment at the old rate in the North and Central regions and implemented mass tax payment with a poll tax rate of 2.5 dong... In the South alone, the poll tax increased from 5.58 dong (in 1913) to 7.5 dong (in 1929).

“The total tax revenue from 1912 to 1929 was three times higher than the previous period. In normal years, this tax was a heavy burden on the people compared to their meager income. In years of hardship, crop failure, and economic crisis, the burden became especially terrible. Calculated per capita, regardless of age, each Vietnamese person had to pay 8 dong in tax, equivalent to 70 kg of first-class white rice at that time.”(4)

The 1929-1933 world economic crisis had a strong impact on the economic and social situation in Vietnam. Many factories, enterprises and plantations reduced their production scale. Tens of thousands of workers were laid off or worked for low wages. Millions of farmers lost their land and had to live in poverty, and the lives of other social classes were also affected.

“Workers’ wages never exceeded 2 to 2.5 francs per day. Men earned 1.75 to 2 francs, women 1.25 to 1.5 francs, children from 8 to 10 years old received 0.75 francs… On the plantations, workers had to work 15 to 16 hours a day… Farmers had to pay high taxes, heavy fees and usury. One tax in 1929 was equal to 50 kg of rice, in 1932 it was 100 kg, in 1933 it was 300 kg… Farmers had to borrow from landlords at any interest rate to survive and then had to sell all their meager assets, even their children, to pay the taxes and repay”.(5)

Entering the period 1936-1939, the French colonialists continuously increased the poll tax. In the North, from 1937 onwards, the poll tax was divided into 14 levels. In the Central region, Decree No. 81 dated November 16, 1938 stipulated that all male citizens who turned eighteen years old were subject to a certain poll tax and were divided into many tax rates. In the South, the poll tax was reduced from 7.5 dong to 4.5 dong and 5.5 dong but an additional income tax was imposed. In the closing speech of the Central region's House of Representatives read on September 21, 1938, the issue of taxation was also mentioned, which was to request the protectorate government to implement democracy and reduce taxes for the people:“We, the people of Central Vietnam, have a small land area and a large population, heavy taxes, and a very difficult life. Yet the government is increasing taxes at this time. We are worried that if we encounter danger, will we be able to bear it?”

Thus, before 1945, heavy taxes made people's lives more miserable and miserable. Besides the personal tax, the French colonialists continued to increase unreasonable taxes such as land tax, salt tax, alcohol tax, opium tax, residence tax, house tax, irrigation tax, trade tax, etc.

People were also forced to do heavy labor, buy government bonds, defense coupons, contribute money to the war fund and endure many tricks of excessive surcharges from village chiefs and tyrants, and bad customs of weddings and festivals...

The process of polarization between rich and poor in the country took place rapidly, class conflicts, especially the conflicts between the Vietnamese people and the ruling French colonialists, became increasingly fierce, creating an important premise for victory in the August Revolution of 1945, seizing power throughout the country.

On September 3, 1945, at the first meeting of the Provisional Government, President Ho Chi Minh proposed to immediately abolish three types of taxes: poll tax, market tax, and ferry tax. On September 7, 1945, on behalf of the President of the Provisional Government, Minister of the Interior Vo Nguyen Giap signed Decree No. 11 to abolish poll tax and affirmed that poll tax was an unreasonable tax.

The Nghe Tinh Soviet Museum is currently displaying, preserving and promoting the value of many unique collections, especially the collection of pre-1945 personal tax card artifacts. The collection includes 6 artifacts, dating from 1931 to 1942, during the period when the French colonialists applied personal tax in Vietnam. These artifacts are the result of a long-term collection process by museum staff. Specifically as follows:

- Personal income tax card issued by the French colonial government to Mr. Nguyen Thanh Vien, Thanh Thuy village, Xuan Lieu commune, Nam Dan district, Nghe An province. Personal income tax type 2 dong 80 xu. Valid from July 1, 1931 to June 30, 1932.

- Personal tax card issued by the French colonial government to Mr. Nguyen Loi, in Thuong Nga village, Lai Trach commune, Can Loc district, Ha Tinh province, 41 years old. Personal tax type 2, 50 cents. Valid from July 1, 1931 to June 30, 1932.

- Personal income tax card issued by the French colonial government to Mr. Nguyen Tam in Phuc My village, Van Vien commune, Hung Nguyen district, Nghe An province, 36 years old, occupation: farmer. Personal income tax type 2, 975 dong. Valid from July 1, 1935 to June 30, 1936.

- Personal income tax card issued by the French colonial government to Mr. Nguyen Dinh Luong, Thuong Trach village, Thuong Dien commune, Huong Khe district, Ha Tinh province, 44 years old, farmer. Personal income tax type 2, VND 9125. Valid from July 1, 1935 to June 30, 1936.

- Personal income tax card issued by the French colonial government to Mr. Le Lieu, Tinh Diem village, Huu Bang commune, Huong Son district, Ha Tinh province, 54 years old, working as a laborer. Personal income tax type 2, 75 dong. Valid from July 1, 1937 to May 1938.

- Personal income tax card issued by the French colonial government to Mr. Tran Van Tieu in Tri Le village, Dang Son commune, Anh Son district, Nghe An province, 30 years old, working as a coolie. Personal income tax of 1 dong 30 xu. Valid from July 1, 1941 to June 30, 1942.

From artifacts with specific and authentic content, the collection of poll tax cards at the Nghe Tinh Soviet Museum is a valuable source of historical documents serving research, display, education... contributing to introducing and depicting the social picture in a historical period of the nation. Thereby, helping the public see the suffocating, miserable life of farmers due to tax collection, especially poll tax under the colonial and feudal rule before 1945. The Nghe Tinh Soviet Museum will continue to research, preserve and promote the value of the collection, widely introducing it to domestic and foreign visitors.

Note:

1, History of the Nguyen Dynasty: A New Approach, University of Education Publishing House, 2005. p.173

2,3, Outline of Vietnamese History, Volume II, Education Publishing House, 2000, p.115. (Ibid)

4, ibid., pp. 220-221.

5, ibid, p.298.

.jpg)

.jpg)