The secret negotiations about Hong Kong's fate more than 20 years ago

The British succumbed to China's determination and agreed to return Hong Kong in a secret negotiation before 1997, without the presence of Hong Kong people.

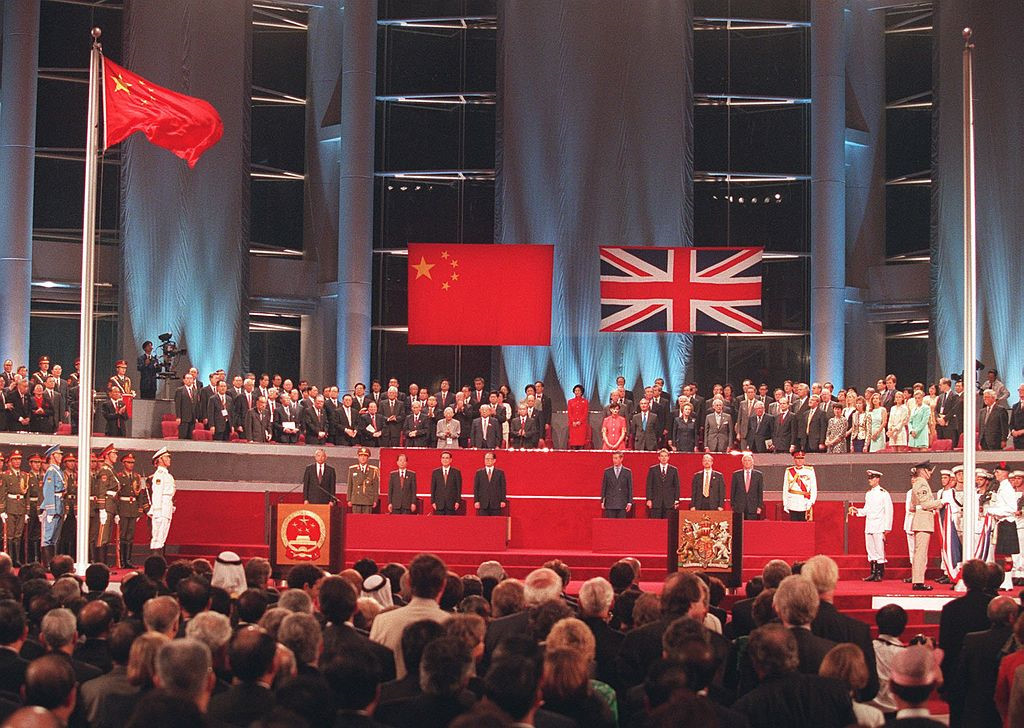

On the pouring rain of June 30, 1997, the British flag was lowered for the last time in Hong Kong, making way for the flag of the People's Republic of China. The British left their last major colony, ending a century of "the sun never setting on the United Kingdom".

The handover ceremony and Hong Kong's fate were decided on December 19, 1984, while secret negotiations between Britain and China began before the 1980s.

|

| The Chinese flag was raised at midnight on June 30, 1997, ending 156 years of British rule in Hong Kong. Photo: AFP. |

Land lease contract expired

The land that is today the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region of China was placed under British rule through three treaties in 1842, 1860 and 1898.

After the Qing Dynasty's defeat in the First and Second Opium Wars, Hong Kong Island and Kowloon Island were ceded to Britain. In 1898, the Qing Dynasty continued to lease the land that would become the New Territories (Hong Kong) to Great Britain for a period of 100 years.

Unlike Hong Kong Island and Kowloon, the New Territories were always destined to return to China on June 30, 1997.

As the 1990s approached, the British knew they would have to reckon with Hong Kong's future.

Like most British colonies, Hong Kong's future does not include independence. After joining the United Nations in 1971, China successfully lobbied to have Hong Kong removed from the list of "Non-Self-Governing Territories".

This is the group that the United Nations General Assembly declared would "promote measures aimed at achieving full freedom and independence."

Initially, the British government was confident and eager to continue administering Hong Kong even if sovereignty were returned to China. According to documents later declassified by the British government, in the late 1970s, Prime Minister Thatcher's cabinet wanted to extend indefinitely the lease of the New Territories to "continue British rule after 1997 if the Chinese accepted", or at least they wanted to retain Hong Kong Island and Kowloon.

Beijing rejected that proposal.

|

| By the end of the 20th century, Hong Kong had become one of the world's largest financial centers. He feared an uncertain future for Hong Kong would undermine the city's standing with investors. Photo: AFP. |

Stumbled in Beijing

In April 1982 in Beijing, during a meeting with Mr. Edward Heath, then former British Prime Minister, Chinese leader Deng Xiaoping proposed the idea of "One Country, Two Systems", allowing Hong Kong to retain its "capitalist" economy and freedoms while sovereignty was returned to Beijing.

In late 1982, British Prime Minister Thatcher arrived in Beijing, becoming the first British Prime Minister to visit China and formally beginning negotiations on Hong Kong. On September 23 of that year, she met Premier Zhao Ziyang at the Great Hall of the People.

Notes from the meeting said Mrs Thatcher warned that returning Hong Kong to China, then an economy that had just begun to open up, would be a "disaster" that would drive away investors and cause the collapse of a world financial center like Hong Kong.

Mr. Zhao said there were two factors to consider when negotiating Hong Kong's future: sovereignty and the city's stability and prosperity. "If forced to choose one, China will put sovereignty above stability and prosperity," the transcript quoted the Chinese premier as saying.

The next day, Deng Xiaoping, the diminutive man who held supreme power in China at the time, warned Mrs Thatcher that “in one or two years, China will officially announce the resumption of Hong Kong.” It was also the day Margaret Thatcher tripped and nearly fell in front of the Great Hall of the People in Beijing.

Negotiations continued after Mrs Thatcher left Britain and concluded with the 1985 Sino-British Joint Declaration, under which Hong Kong was returned to China under "One Country, Two Systems" status, ending 156 years of British rule.

|

| Chinese leader Deng Xiaoping and British Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher meet at the Great Hall of the People in Beijing in September 1982. Photo: AFP. |

Deng Xiaoping's Will

Information about the Hong Kong negotiations has been revealed mainly through British government documents, which are made public under regulations that require cabinet documents to be declassified after 20-30 years. These documents often do not directly quote Chinese officials, but are mainly notes from the British side.

Percy Cradock, British Ambassador to Beijing from 1978 to 1983, described China's leaders as "old men with rigid ideas, full of dogma and national pride".

In his book The End of Hong Kong: The Secret Diplomacy of Imperial Retreat, Robert Cottrell describes Deng Xiaoping's calculations as follows:

“If he agreed to let the British stay in Hong Kong after 1997, Deng said, he would be no different from the Qing traitors who ceded land to Britain under illegal and invalid treaties. He could not do that. China must restore sovereignty over Hong Kong. And sovereignty must include governance. The British flag must go. The British governor must go.”

|

| The last Governor of British Hong Kong, Chris Patten, receives the Union Jack after it was lowered at his residence on the afternoon of June 30, 1997. Photo: AFP. |

The talks were repeatedly pushed to the brink of collapse as officials from both sides used harsh words to criticize each other. However, Britain always worried that China would pull out of the negotiations.

Declassified documents show that the British feared that if Deng "could not reach a satisfactory agreement with the British authorities, he might decide to retake Hong Kong early".

In a 2007 interview, former Prime Minister Thatcher admitted for the first time her regrets about facing the "untenable" situation in the Hong Kong negotiations. The former Prime Minister confessed that she watched with sadness as the British flag was lowered in Hong Kong in 1997.

"I wanted to continue British rule. But when that became impossible, given our circumstances, the only chance I had left was to retain Hong Kong's unique features by accepting Mr. Deng's ideas," she said.

However, the “chief architect” of the “One Country, Two Systems” model could not wait to see his idea come to fruition. Mr. Deng Xiaoping died on February 19, 1997, just five months before Hong Kong returned to China.

Hong Kong people on the sidelines

Hong Kong's more than 5 million people had little say in the negotiations between the British and Chinese governments. Emily Lau, former chairwoman of Hong Kong's Democratic Party, said Hong Kongers knew that "all they (the British) cared about was trade. The fate of Hong Kong people was secondary."

Lau pointed out that in the negotiations between Britain and Argentina over the Falklands, the residents of this island, which has “1,800 people and hundreds of thousands of sheep,” still had a seat at the negotiating table. Meanwhile, Hong Kong people were not involved in the negotiations between Britain and China.

Last-ditch efforts by a group of lawmakers in Hong Kong's Legislative Council to represent the views of the city's people have been fruitless.

|

| Victoria Harbour (Hong Kong) a few days before the city was returned to China. Photo: AFP. |

“Both the British and Chinese governments have publicly called on the people to contribute their views to the negotiations. But how can they express their views if they know little or nothing about what is going on?” said lawmaker Wong Lam at a hearing of the Hong Kong Legislative Council in 1984.

However, Hong Kong people were later involved in drafting the Basic Law, a mini-constitution that would provide the legal framework for Hong Kong to operate under the “One Country, Two Systems” model. Hong Kong’s last governor, Chris Patten, also reformed the Legislative Council electoral system to increase the number of directly elected lawmakers.

According to Zing.vn

| RELATED NEWS |

|---|