'Madam Nhu Tran Le Xuan': The birth of a royal mother

The woman covered in sweat and blood lying on the table was Princess Truong, Nam Tran, a member of the royal family.

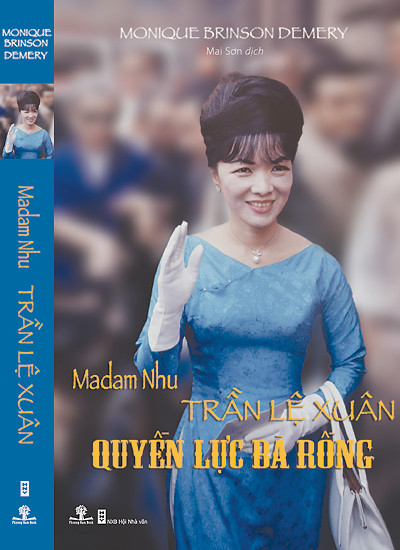

The book Madam Nhu Tran Le Xuan - Dragon Lady's Power about the life of Mrs. Tran Le Xuan (Mrs. Nhu, 1924-2011) has just been released to readers. Mrs. Tran Le Xuan is the wife of Mr. Ngo Dinh Nhu, a government advisor in the former South Vietnam.

On the occasion of the book's release, VnExpress publishes chapters three and four of this 16-chapter book. The excerpts are named by the editorial board.

Part 1:The Royal Mother's Childbirth

The more I learned about Madame Nhu’s early years, the less glamorous her family’s past seemed. The smiling faces of the elderly couple in a Washington newspaper photograph from 1986 were hard to reconcile with the somber portrait of Mr. and Mrs. Chuong that emerged. The “miserable” pieces of Madame Nhu’s childhood memories fell into place when I understood that no one, other than her parents, of course, had any inkling that this tiny baby girl, born in a Hanoi hospital on August 22, 1924, would eventually become something important.

A traditional birth would take place at home with a midwife who would say the creature was unwilling to be born because the baby was in a breech position, and therefore refused to slide down the birth canal. She would reject forceps, those tiny instruments and modern science, as interfering with the will of heaven. A midwife would abandon the baby, pale, weak, mute, and motionless, to whatever crossroads between heaven and earth the un-reincarnated souls wander.

|

Book cover about the portrait of Mrs. Tran Le Xuan. The book is published by Phuong Nam Book Company in association with the Writers Association Publishing House. |

But there was no midwife that day. The baby would be a boy. The mother was so sure of it that she arranged for the birth to take place in a hospital. She had endured the horror of the long labor, knowing it was worth it - for a son.

The French doctor was probably afraid of being reprimanded if anything went wrong. It was the first time he had delivered a Vietnamese baby since arriving in Indochina, but this was an unusual case.

The woman covered in sweat and blood lying on the table was Princess Truong, Nam Tran, a member of the royal family.

The beauty of this fourteen-year-old girl was so rare that she later won a medal from the French admirers, who nicknamed her “The Pearl of Asia”. Although she was taught the arts of housekeeping, as well as singing and embroidery, she never had to lift a slender finger, except to ring the bell to summon the servants. Her most important duty as a wife was to bear her husband a son to inherit his estate.

Her husband came from a powerful landowning family. As the eldest son of a provincial governor in French Tonkin, Mr. Chuong had been given all the best things in life, from a Western education to a bride of royal lineage. His Tran family was related to the king, so Mr. Chuong was also a distant relative of his wife.

The French doctor must have felt immense pressure to save the pale form that had finally emerged from the bloody, viscous membrane. This was his chance to prove himself—and the superiority of Western medicine. He gripped the baby’s ankles and repeatedly spanked the tiny buttocks until the first cries escaped.

That cry was the baby's first greeting to the world. It was a girl.

What did a young mother of fourteen like Mrs. Chuong do with her newborn child, a lump of flesh with a red face, crying loudly in her arms? When she was born, there was little reason to believe that her fate would be any different from that of centuries of women who had come before her. In the East Asian Confucian tradition, sons were expected to care for their parents in their old age, and only sons were important in the Vietnamese practice of ancestor worship. A traditional Vietnamese proverb summed up the frustration of having a daughter: “Nhat nam viet huu, thap nu viet vo,” or “A hundred daughters are not worth a son’s testicles.” On the wedding day, the man brought home a possession more precious than all others: a daughter-in-law, who would not be freed from her role as a true servant of her husband’s family, especially his mother, until she had a son. The vicious cycle continued.

|

Mrs. Tran Le Xuan (right) and her mother, Mrs. Than Thi Nam Tran. Photo archive. |

Mrs. Truong had already given birth to a daughter. Her first child, Le Chi, had been born less than two years earlier, and Mrs. Truong had convinced herself that this second child would be a boy. She was so sure of it that she bought many boyish toys and clothes.

This second daughter only delayed Mrs. Truong’s freedom. Until she gave birth to a son, she was the lowest in the hierarchy of her husband’s family. Moreover, her mother-in-law had made some ominous threats. She wanted her son, Mr. Truong, to take a concubine if this second child was not a son. Mr. Truong, after all, was the eldest son of the prestigious Tran family—he should take every opportunity to continue the family’s greatness with his own blood. Polygamy had been part of the cultural tradition in Vietnam for centuries. A woman who only bore daughters, whether loyal daughters-in-law or not, was of little value. The failures should be wiped out as quickly as possible.

It was a dismal prospect for a fourteen-year-old woman like Mrs. Truong. If her husband took a second wife, and if that woman succeeded where she had failed, in giving his family a son, Mrs. Truong and her daughters would have to live the rest of their lives in subservience. She soon made up her mind that she would have to do this again—and again—until she had the son she longed for. And the son they expected of her.

The newborn daughter was named Le Xuan. Even though it wasn’t spring yet. August in Hanoi is usually the start of autumn, and that year was no exception. It seemed like the first days of autumn had brought a chill to the city, a refreshing breath after the long, sultry summer days. The willow branches gently touched the surface of the lake, inviting a gentle breeze to dance in the leaves, and the city’s residents poured into the open air to enjoy the brief mild season before the cold winds from China swept in.

Little Le Xuan and her mother did not enjoy a single moment of that happiness. Vietnamese tradition required that newborns and their mothers be confined to a dark room for at least three months after birth. The room was a cocoon for mother and baby. Even bathing practices were restricted. This custom arose from practical concerns about the mortality risks of newborns in the tropical delta, but in reality the gloomy scene after birth must have been suffocating. Except for the traditional healer and fortuneteller, who were indispensable figures, Mrs. Chuong’s visitors were limited to the closest members of the family.

The family fortuneteller was one of the first to see the baby. His job was to predict the baby’s fate by comparing the birth date, zodiac season, and birth hour with the positions of the sun and moon, not forgetting to take into account passing comets. Most likely, in an attempt to cheer up the poor mother, who had been locked in a dark room for three months with her unwanted little girl, the fortuneteller exclaimed of the child’s fate: “It’s beyond imagination!” The child, he told a trembling Mrs. Truong, would climb to great heights. “Her star could not be better!” The girl would grow up believing in her own destiny, and the brilliant prophecy would make her mother deeply jealous. The result was a life of strained mother-daughter relationships and endless suspicion.

To be continued...

According to VNE

| RELATED NEWS |

|---|