Remembering Tet years ago when I met Uncle Ho

(Baonghean.vn) - In previous years, during peacetime, when receiving groups of children, Uncle Ho spent many hours, but that time we were only able to be with him for about half an hour. He gave us general advice, he gave candy to each of us, then due to urgent work, he said goodbye.

That Tet, At Ty, I was a 6th grade student, school year 1964-1965, Ly Thuong Kiet Secondary School. That Spring in Hanoi was very cold, only 10, 11 degrees and frosty, so the Tet holiday was extended, until February 8 (lunar calendar is January 7), when the sun and warmth returned, we returned to school. But the day before, February 7, 1965, the US imperialists massively bombed Vinh, Vinh Linh, Dong Hoi, starting a total war of destruction, so after the school opening ceremony we did not go to school but started repairing the anti-aircraft tanks that had been dug in the school yard since August 5, 1964.

The next day, the teachers and students of grade 7 continued to dig trenches and build mounds, while we, students of grades 5 and 6, also went to school, but only to get on the van to go to the Presidential Palace.

Back then, in the years before the war, Hanoi children were often organized by the City Youth Union to visit Uncle Ho's house, but always in May, in the summer, at the end of the school year. As for us that time, in the middle of the school year, we had never done so before. And also because it was sudden, the school did not evaluate and classify, so our whole class, regardless of whether we were excellent or advanced, enjoyed unexpected happiness. We dressed the same as we did every day when we went to class, without having to prepare or decorate anything...

The spring weather was warm and sunny. Roses were blooming brightly along the paths. We, the 100 eleven and twelve year old children, were ecstatic and spread out in the vast garden. The quiet space of the Presidential Palace was stirred by the noise of the crowd of students running, laughing, playing and singing. The palace door on the high platform was also opened for the children to rush up more than 20 steps and play inside the spacious marble-paved lobby.

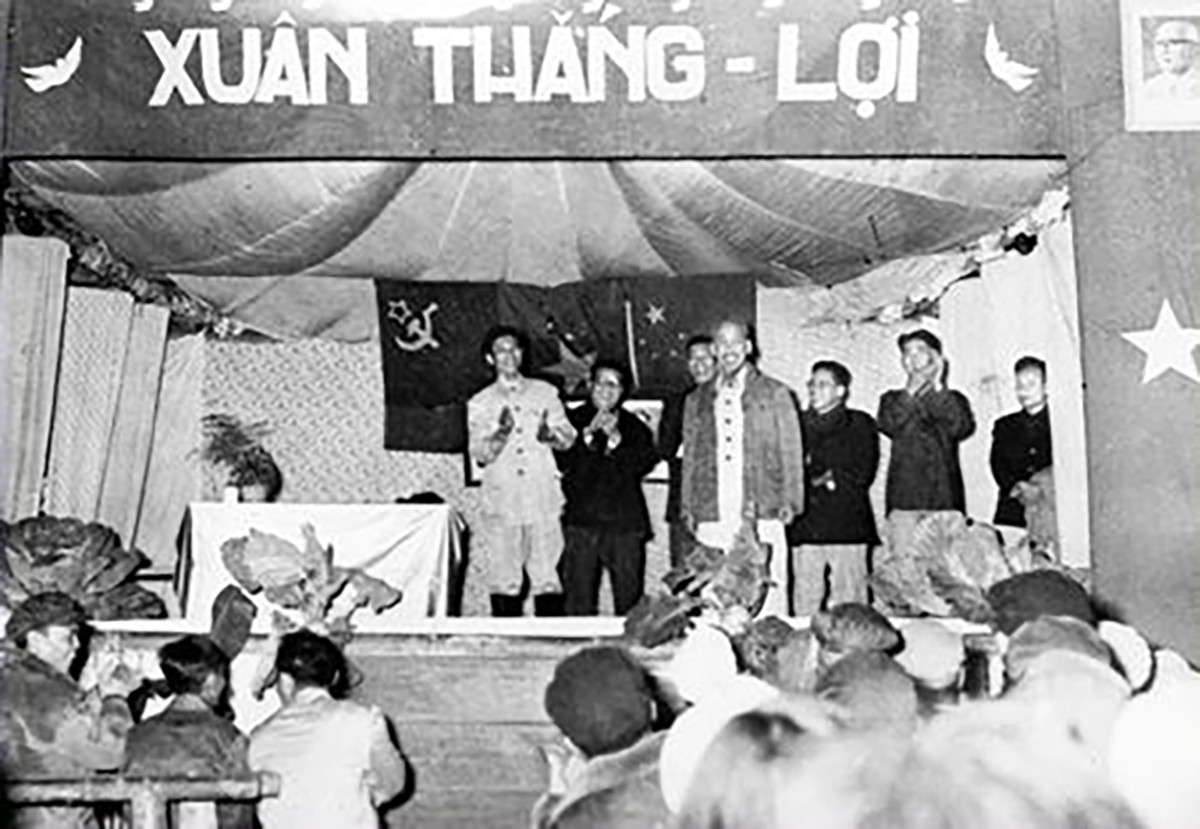

In the afternoon, we were gathered together, lined up in pairs to go to the stilt house. At that time, people were not allowed to go up the stairs of the stilt house to visit Uncle Ho's study like today. We sat on the stone benches for children surrounding the yard, eagerly waiting to welcome Uncle Ho down. After about ten minutes, Uncle Ho arrived. But he was not coming down from the stilt house. He was returning from the Party Central Committee. Walking with him was the Soviet Prime Minister. There were no guards or interpreters, just Uncle Ho and the guest among the crowd of children cheering and rushing to gather around.

I remember, when the noise of us children had subsided, Uncle Ho said, "Sorry, the meeting had to be extended so I came back late and made you wait." He introduced us to the Prime Minister. He said, although time was very tight, comrade Aleksey Nikolaievich Kosugin still wanted to go with Uncle Ho to the Presidential Palace to meet the children. He let the guest speak. The Prime Minister spoke slowly and emotionally but not at length. I remember that at that time it was not the interpreter, but Uncle Ho who directly translated for us the sincere and intimate words of the Soviet guest speaking to the Vietnamese children at almost the first moment of the national resistance war against America.

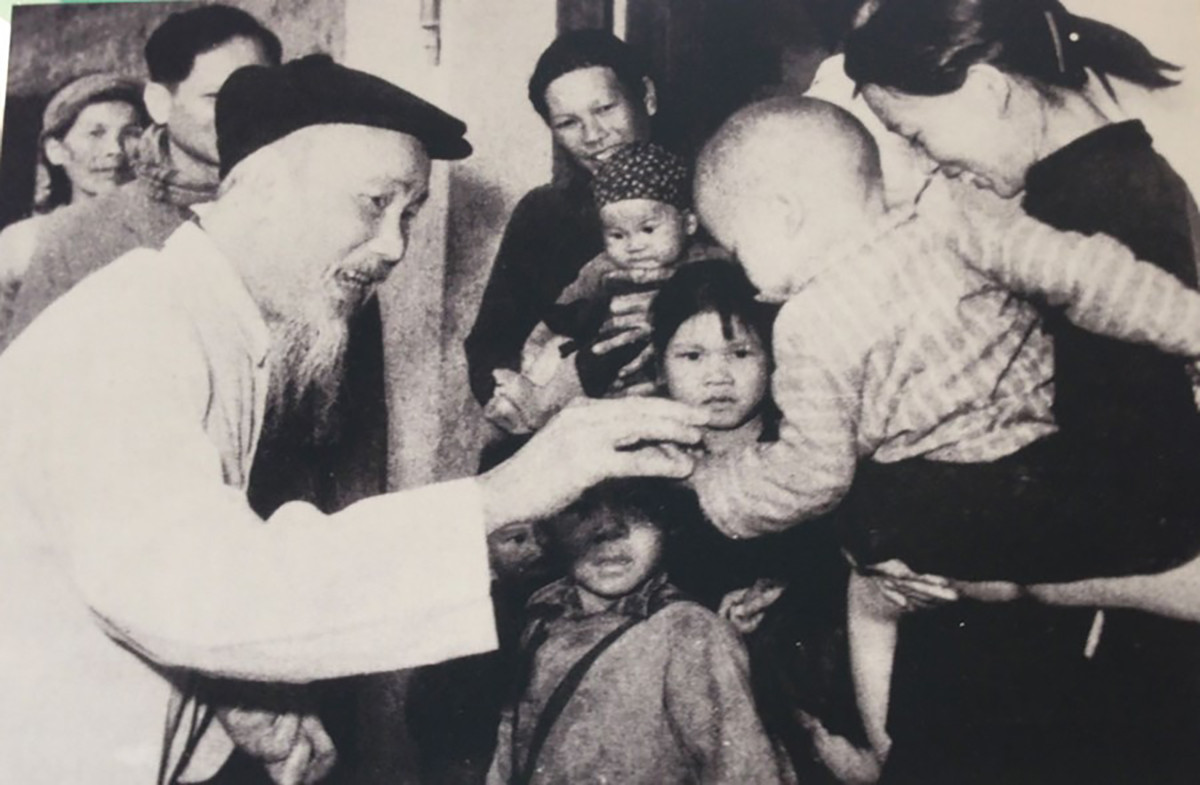

In previous years, in peacetime, when receiving groups of children, Uncle spent many hours, but that time we were only able to be with him for about half an hour. He gave us general advice, he gave candy to each of us, and then, due to urgent work, he said goodbye. Even though he was in such a hurry, Uncle still managed to notice one of us who was huddled around him. That was Nguyen Kim Thai, a classmate who sat at the same table with me every day.

Thai was an orphan and his mother worked as a scrap collector. His family was very poor, lacking food and clothing. Therefore, Thai was very small, short, skinny, dark-skinned, dressed shabbily, and wore worn-out rubber sandals. But perhaps because he stood out like that, that morning, even though he was lost in the crowd of friends, Thai was still noticed by Uncle Ho. After saying goodbye to everyone, Uncle Ho stopped and kindly spoke to Thai alone for a while longer...

After that unforgettable morning of February 9, 1965, we students said goodbye to Ly Thuong Kiet school, Hanoi and each other, each going our separate ways, evacuating to the countryside. Many years later, when the first destructive war (1965 - 1969) ended, we had the chance to meet again.

The group of school children who had unexpectedly enjoyed the happiness of meeting Uncle Ho on the last day of peace, after 4 years, were all strong and brave young men, with the same iron determination, unanimously going to war. Nguyen Kim Thai and I were together again, in the same battalion of new soldiers, the same company, the same platoon. One night on guard duty together, Thai told me that, back then, just two days after the day our whole class visited the Presidential Palace, Thai had received gifts from Uncle Ho. They were a cotton jacket, a sweater, a scarf, and a pair of shoes. Uncle Ho's personal secretary brought the gifts to Thai's house, deep in the alley of the poor Kim Ma street.

After 4 months of training for new recruits in Bai Nai, we were assigned to different units. Thai, probably because he was very good at Math, was assigned to the missile corps, fighting in battlefield A.

My friend, Nguyen Kim Thai, died in December 1972, in Hanoi, during the 12-day and night campaign of American B52 bombing. That was our generation. The generation of September 1969 warriors.

When I think back to 1969, my mind always sees a curtain of white rain, a red-hot Red River, immense and rolling, rushing heavily as if about to sweep away both banks. Autumn was a difficult season, with continuous rain and storms. Every year was like that, but it seemed that the deeper we went into the war, the greater the flood of the Red River each year. Before the Full Moon of July, it was already very dangerous, after it was even more dangerous. By mid-August, the young men and women of my whole street were mobilized to protect the dike. By National Day, the water level had dropped a lot, but we still tried our best to continue raising and thickening the weak dike section at the intersection of the Duong River and the Red River. It wasn’t until dawn on September 3 that we took turns. The eight of us were sleeping in the shack when we were woken up, put on a car to return to the city. We got back in the car and slept again…

At that time, it was about 6am, our car was on Long Bien Bridge. Both directions of the only bridge across the Red River were crowded, people and vehicles jostling, moving slowly with each step, each turn of the wheel. But there was no car horn, no bicycle bell, no voice, no laughter, it seemed like there was not even the sound of footsteps even though the stream of people was still moving non-stop. Faces wet with rain and eyes half-closed, but in just a moment I realized that everyone, all of them, thousands of people, along the entire length of more than two kilometers of the bridge across the rushing water were walking and crying, or rather, crying silently, crying without making a sound. Because it was extremely quiet. People walking along both sides of the bridge railing, walking empty-handed or carrying burdens, people pushing bicycles, people standing on the beds of trucks, people sitting in passenger vans. Soldiers. People from the city. People from the countryside. Walking and crying, in the rain.

The few of us in the truck bed and the driver in the cabin were all people who had fallen from the sky. For a whole week, we clung to the dike, wading through mud and soil, falling asleep whenever we had a break, we were isolated by the rain and floods from the radio and the world. However, just for a moment, seeing the simultaneous grief of two large streams of people walking in the rain, we immediately understood what was happening.

"Uncle Ho...". One of us whispered, hesitantly. We weren't sure what we were thinking, but we all felt it for sure. Because for us, even in that period of great suffering, such a great, heavy, deep, and universal pain could only be due to one single reason in the world. At that moment, a train engine, without any cars, running alone across the bridge, from Hanoi to Gia Lam, suddenly blew its whistle when it passed us. You could say that the train engine let out a sigh. I didn't just imagine it later, but it really did, it was a sigh, like that of a human being. Immediately, a tugboat anchored somewhere on the side of Pha Den also blew its whistle. Then from Gia Lam Station, many other locomotives simultaneously blew their whistles. The hoarse, painful whistles echoed in the rain...

President Ho's passing, that great loss made the whole people stand together more than ever, turning grief into strength. Hearing those words, people today may think they are literary and exaggerated. But for those who lived in the heart of Hanoi in the fall of 1969, when they hear those words that seemed like slogans, they will clearly see again the mood, will, determination, and mettle of themselves, their families, their friends, and their neighbors that day.

In September 1969, the new recruits' gathering day, which was supposed to be on the 7th, had to be postponed to the 15th. One reason was because of our brothers' wish to stay in Hanoi during the National Mourning Week so that we could line up with everyone else at Ba Dinh Hall to pay our respects to Uncle Ho; two was because the number of young people volunteering to join the army increased immensely during those days. They volunteered resolutely, wanting to leave immediately, not accepting to wait until the next batch. Of course, not only in Hanoi but also in the whole country and in every locality.

The new recruits that fall were called batch 969. This was a batch in which many were the last sons or only sons of their mothers, meaning those who were not eligible for military service but still decided to leave to fight. In our new recruit battalion at that time, there were also some classmates who had received notices to enter universities in the country and abroad. Some were already on the train to the Vietnam-China border, and upon hearing the news of Uncle Ho's death, they immediately got off the train and returned to join the army...

For those of us, born in 1950, 1951, 1952, enlisted from around 1968 onwards, if asked which year was the fiercest in our military life, they all said 1972. However, the most arduous and dangerous year was 1969 - 1970. This was the period after Mau Than, which many people also called "the period after Uncle Ho's death".

Until now, I still often wonder: How, thanks to what, can my country, my compatriots, my comrades and myself endure, stand firm during days and months that far exceed human endurance, then overcome, pull ourselves up and rise up, and finally reach the day of Total Victory, April 30?

***

On the morning of April 30, 2023, President Vo Van Thuong had a cordial meeting with the veterans of the B3 Front of the 3rd Corps at the Presidential Palace, thanks to which I was able to visit Uncle Ho's house for the second time in my life. The previous times I visited the Mausoleum, I did not go deep into the grounds of the Presidential Palace, so this time, after 58 years, I and my friends climbed the 21 steps to the high platform and through the wide-open palace door to enter one of the most sacred and noble buildings of the country.

21 marble steps, 58 years. Back then, we were young soldiers with red scarves around our necks, happily rushing up the steps. Now, we are old, gray-haired soldiers, with so many emotions in our hearts, silently and leisurely walking up together. Each marble step, each step, represents years, stages of life.

Spring sky, high and sparse clouds gently drifting. In the vast garden of the Presidential Palace, the wind sometimes calms down, sometimes rises like the climax of a song. Years pass, the sea changes, the stars change, but here, the earth and the people's hearts are eternal in the Ho Chi Minh era. Together we listen in our hearts to Uncle Ho's words from long ago, on that stormy and stormy Spring day of the Year of the Snake, advising and instructing the young grandchildren. Uncle Ho's voice, my homeland of the Central region, forever echoes in the lives of our generation, the generation of "thousands of troops marching on Uncle Ho's path".