The Race to Find a Coronavirus Vaccine: Run, Don't Walk!

(Baonghean.vn) - Scientists are racing to produce a vaccine to treat the latest strain of the Corona virus. Even if they are too late in this outbreak, their efforts will not be wasted.

|

| Illustration: Economist |

Efforts to find a vaccine

In recent weeks, Google searches for “contagious disease movie” have spiked. In the 2011 film, a virus spreads rapidly around the world, killing 26 million people. The plot follows scientists’ frantic efforts to create a vaccine. 133 days after the first case, they succeed.

In the real world, most recent vaccines take years to develop. Some take more than a decade. Others, such as the vaccine for HIV, the virus that causes AIDS, still stump scientists. But technological innovations and a more streamlined development process could dramatically reduce the time it takes to produce a vaccine against a new pathogen that has the potential to cause an epidemic.

The novel coronavirus that emerged in the Chinese city of Wuhan in December 2019 has presented vaccine makers with an urgent test. The virus has so far killed more than 800 people and infected more than 37,000. Scientists in China released the genetic sequence of the Wuhan virus on January 12, less than a week after they isolated it from a patient with a mysterious respiratory illness. By the end of January, several groups around the world had begun researching vaccines using the genetic data. To ensure safety, the first clinical trials on humans could begin as early as April. With luck, a vaccine could be ready within a year. Next week, the World Health Organization (WHO) will convene a global meeting to set the research agenda. The agency would unify rules, or protocols, for trials and results, prioritizing medical advances.

There have been races to develop new vaccines before. The 2013-2016 Ebola epidemic in West Africa challenged the world in many ways, but most importantly, in the need to accelerate the discovery of new treatments. Organizations and institutions that normally work slowly and in isolation joined forces to complete the task more quickly. Drug regulators from the United States and Europe, pharmaceutical companies, volunteer organizations, experts, and the WHO worked closely to accelerate the trials and technologies needed. They succeeded. The 2018 Ebola outbreak in the Democratic Republic of Congo, now waning, was largely contained by the widespread availability of vaccines. This scientific acceleration is happening again, “even faster,” as Seth Berkley, the boss of GAVI, a vaccine company, puts it.

|

| The new strain of coronavirus under a microscope. Photo: Doherty Institute, University of Melbourne |

Even if a vaccine is available within a year, it will be too late to stop the current outbreak in China. But it could help other countries. Fears are growing that the Wuhan virus will spread further and become a seasonal illness around the world, like the flu. China’s extraordinary efforts to contain the virus, including quarantining more than 50 million people, could keep the disease at bay in other countries until next winter. It’s too early to say how deadly the Wuhan virus will be. But if it is at least as bad as seasonal flu, a vaccine for those most at risk could be vital. In 2017-2018, more than 800,000 people were hospitalized and about 60,000 died in the United States alone from the flu.

The effort to develop a vaccine for the Wuhan virus is being led by the Coalition for Epidemic Preparedness Innovations (CEPI), which was established in 2017 after the Ebola outbreak in West Africa. CEPI’s goal is to prepare the world for future outbreaks, regardless of the disease. The goal is to have a vaccine for a previously unknown pathogen ready for human testing within 16 weeks of its identification. To that end, several university research centers and biotech companies it funds have been working on “ready-to-use” vaccine technology for multiple pathogens. This allows the genetic sequence of a specific pathogen to be inserted into an existing molecular platform, forming the basis of a vaccine.

Previously, experimental vaccine research required storing the actual virus, which would be treated to make it less harmful but still capable of stimulating the immune system to produce antibodies—proteins that fight off viruses in the environment—in case of infection. Obviously, working with a potentially lethal virus is difficult, requiring special facilities for storage and extensive procedures to prevent the virus from escaping or infecting scientists.

Genetic sequencing has made the process faster, safer, and easier. Researchers can create synthetic versions of virus parts to study vaccines without needing samples of the finished pathogen.

Scientists have developed vaccines for other viruses, including Zika, Ebola and two coronaviruses – SARS and MERS – using such technology. Research on vaccines based on the two “cousins” of the Wuhan virus has been particularly useful in recent weeks.

|

| Medical staff spray disinfectant on discharged patients returning to a quarantine area in Wuhan. Photo: AFP |

Widely popular

Once a vaccine is developed in the lab, it is shipped to a factory, where it is turned into a sterile vaccine mixture. This is then divided into vials and checked for contamination before it can be tested in humans. Many such tests are done in petri dishes, a process that can take months. Genetic sequencing could make this much faster. By sequencing the DNA of everything in a vial of vaccine and examining the results, scientists can spot traces of viruses that shouldn’t be there. Vaccine teams in the UK are in talks with the country’s drug regulator about an approval process for such alternative testing methods.

Vaccine development could be accelerated if bottlenecks in the process are removed, according to Sarah Gilbert, who leads a team at Oxford University working on a vaccine for the Wuhan virus. Her team has developed a vaccine template that can be adapted quickly to new pathogens. Researchers can create the first small quantities of a new vaccine in just six to eight weeks, a process that would have taken up to a year in the past. Other teams working on a vaccine for the Wuhan virus are using similar methods, including templates that have already been proven to work.

Faster regulatory approvals could also speed up the process of a vaccine going through clinical trials. Professor Gilbert’s team has already started applying for clinical trials as soon as they start working on the vaccine. They plan to apply for fast-track ethical and regulatory review, which could be granted in a matter of days, as was the case with the Ebola vaccine trials conducted in the UK in 2014. Typically, Professor Gilbert says, this process takes about three months.

|

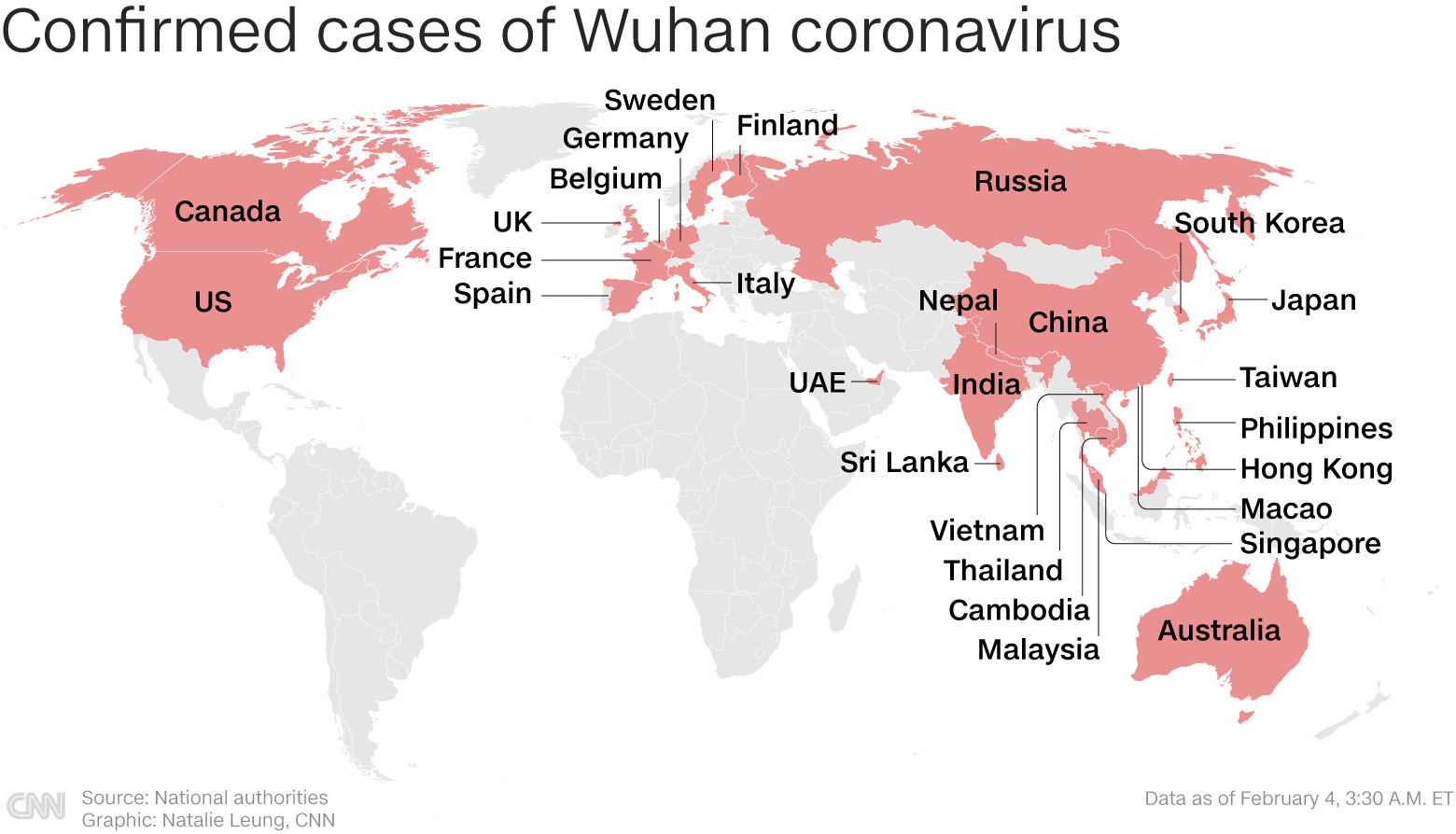

| Countries with cases of Wuhan virus infection around the world. Graphics: CNN |

Even if a vaccine is developed and approved, the rapid rise in Wuhan virus cases in China and its spread to other countries has created a new urgency: preparing ways to quickly produce large quantities of a vaccine. There are few factories that can mass-produce vaccines, so new vaccines often have to “wait and see.” Recognizing this problem, the US government has built its own manufacturing facilities that can quickly produce vaccines in emergency situations. The UK is doing the same.

When CEPI plans its research, it thinks about epidemics in one country, not global ones, according to Richard Hatchett, head of CEPI. Last week, CEPI called for vaccine candidates against the Wuhan virus that can be produced at large scale with existing capacity. On February 3, the organization collaborated with GSK, a large pharmaceutical company, to lend a highly effective adjuvant to the vaccine. An adjuvant is a special ingredient that makes a vaccine more effective by enhancing the immune response, meaning fewer doses of the vaccine or a lower concentration of the key ingredient are needed to prevent disease.

Even if a vaccine can be produced in sufficient quantities, getting it to the people who need it, wherever they are, could be a problem. In theory, a Wuhan coronavirus vaccine would go to those most at risk, such as health care workers, the elderly, and those with conditions that make the virus more deadly, such as people with weakened immune systems. The problem is that politics often intervenes during a global pandemic, and governments where vaccine production facilities are located could commandeer some of it for their own purposes, citing national defense or security.

It’s a problem Hatchett knows all too well; he worked at the White House on health preparedness during the 2009 flu pandemic. That outbreak had a very low fatality rate, but quickly exporting any vaccine before it reached American citizens became a problem. Hatchett is working with the WHO to ensure that Wuhan virus vaccines are produced in multiple facilities around the world, including in smaller countries that can quickly meet the needs of their entire populations.

|

| Medical staff at a field hospital in Wuhan, China on February 5. Photo: Getty |

Groping in the dark

The problems surrounding any potential vaccine make questions about drugs to treat people with severe disease especially urgent. There are no approved drugs for the coronavirus yet, but experimental drugs are in development, with some early data on their use. One drug that has shown promise is remdesivir, made by the pharmaceutical company Gilead. Two randomized, controlled trials are set to begin enrolling patients in mid-February. Remdesivir was developed to treat Ebola but has been shown to be effective against a variety of viruses in laboratory tests. A combination of two drugs commonly used to treat HIV has also shown promise and is now being tested in patients, said Vasee Moorthy, who helps set research and development priorities at the WHO during epidemics.

Randomised controlled trials – in which some people get the experimental drug and some get a placebo – are the gold standard of scientific evidence. These will probably take place in the coming weeks as it becomes clear which drugs show the most promise. Trials with hospitalised patients will probably also include a placebo component. All subjects in the trial will receive intensive care, but some will get the experimental drug. This is because no one knows whether the new drug, which may have side effects, will do more harm than good. The sickest patients may get to try untested drugs.

|

| Laboratory staff in Germany test samples taken from patients suspected of being infected with the Corona virus from China. Photo: AFP |

Such preparations are possible for a new disease. The effectiveness of a drug or vaccine can only be tested during an outbreak. The need to find treatments for the Wuhan virus is understandable. Such efforts have proven effective in the case of Ebola. People are willing to rush vaccines and drugs to treat a disease with a mortality rate of about 70%, as Ebola did. But the calculation must be different for a disease that kills 2% (or less) of those infected. If hasty decisions lead to products that are not completely safe, people’s trust in vaccines could be damaged. The loss to global health could then be a formidable rival to the worst-case scenario of the Wuhan virus./.