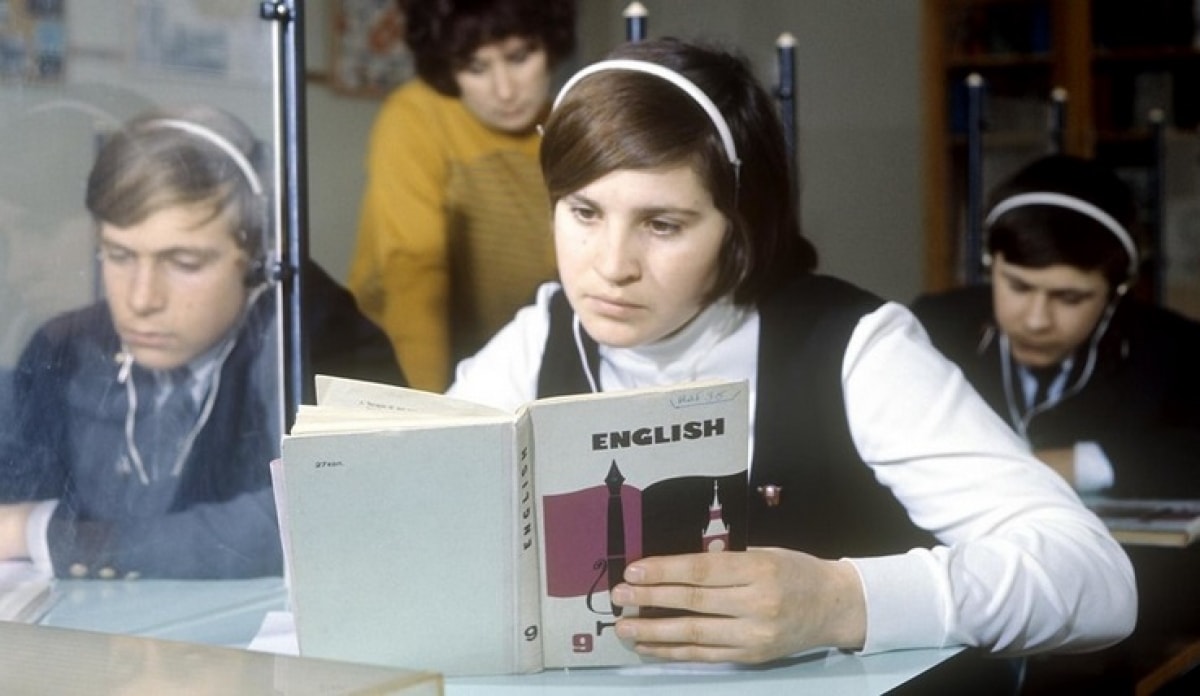

Revealing experiences of learning English in the Soviet Union

Revealed experiences of teaching and learning English in the Soviet Union, where pupils and students did not have many opportunities to practice the language.

Learning a foreign language is like playing a musical instrument. It takes time, practice, and effort. But what happens when you have such determination but no one to practice with? That was the story of millions of Soviet students who learned English knowing that they would never have the opportunity to travel to English-speaking countries or meet native English speakers in their own country.

|

English teaching and learning movement

In 1963, there was a notable Soviet film called “I Walked Around Moscow,” in which a young writer from Siberia complains about his struggle to learn English. Specifically, Volodya Ermakov laments: “I studied English at school for years, but I still don’t understand a word of it.” Another scene in the film shows a waiter at a cafe in central Moscow starting his morning with an English program on a vinyl record player.

The film reflected the cultural trends of the time. In the early 1960s, during the post-Stalin “thaw” period, learning foreign languages became a central part of the Soviet Union’s foreign policy. The Soviet Council of Ministers (i.e., the Government) issued a special decree entitled “On Improving the Study of Foreign Languages,” which gave impetus to the movement. According to this decree, the Soviet Union was expanding and strengthening its international relations with the world. Therefore, the document said, it would be beneficial for specialists in various fields as well as ordinary people to have knowledge of foreign languages.

Schools offering intensive English courses began to mushroom across the country. However, the results were mixed. Several factors hindered the language teaching campaign, including lack of practice, lack of passion, and lack of commitment.

Children generally learn foreign languages faster than adults. Between 1930 and 1950, English, German, and French were taught as second languages in Soviet schools. But why were Soviet students unable to communicate effectively in these languages? The reason is probably because during this period, teachers tried to force students to memorize knowledge by rote rather than foster a passion for the culture of the country where the language was spoken.

“I didn’t want to learn any foreign languages at school,” recalls 69-year-old Natalia. “I was miserable, and if I spoke a foreign language, no one in the world would understand me. It was a disaster.”

Most Soviet people at that time did not have the opportunity to travel abroad and improve their foreign language skills. They were basically unable to communicate in a foreign language in a natural environment with a native speaker. And in the end, their English was basically a word, similar to Latin.

|

The magic of a completely homegrown curriculum

There is a Latin proverb that says “Scientia potestas est”, which means “knowledge makes power”. It was with this in mind that a determined Russian woman named Natalia Bonk devoted herself to promoting the study of English throughout the Soviet Union. This passionate educator devoted her life to promoting the language of Shakespeare in the Soviet Union, creating an English textbook that would become the gold standard in English teaching in the Soviet Union.

It is noteworthy that this brilliant linguist (born in Moscow) had never once set foot outside the Soviet Union. After graduating with a BA in English, she began teaching English courses at the Ministry of Commerce. One afternoon, a senior lecturer attended Bonk’s class. When the class ended, he asked Bonk where she got the English grammar exercises. Bonk replied that she had created them herself, as there was a shortage of English textbooks in the Soviet Union. The very next day, Bonk was summoned to the head of the course and asked to write a new English textbook.

Bonk’s masterpiece appeared in 1960. The first edition was published by a publisher called Globus in Austria. Bonk and his co-authors almost burst into tears when they received the first batch of copies, because at that time the books were “heavy as bricks”. “We were really worried about the weight and thickness of the books, just hoping that our friends would buy them all.”

But then no one expected that this two-volume work (co-written with Galina Kotiy and Natalia Lukyanova) would pass the test of time, becoming a classic in this field. The book has been reprinted countless times since 1960. Students consider it a handbook for learning English. The latest reprint was published in 2019 and is selling like hotcakes in leading bookstores in Moscow.

“I remember Bonk’s book from my university days,” says Vadim, 56. “I borrowed it from a friend many years ago and never returned it. It was a much-readable book. A few years ago, when I was on a business trip to Sweden, I had to look through this 900-page volume and found it really useful. It’s a good book if you want to do a quick reference or brush up on your grammar.”

There are several reasons for the success of this course. The author of the book explains it as follows: “The book is written for people who speak Russian as their mother tongue. The difficulties that arise in the learning process originate from the differences in the grammatical structure of Russian and English, both in vocabulary and phonetics. Of course, there are also many similarities between the two languages.”

Several generations of Soviet students havelearn EnglishBonk's bestseller. For a long time, no textbook could replace Bonk's book in terms of caliber. The book became a "bible" for Soviet students.

Learn English through BBC

Due to lack of environment and means, some Russian youths have tried to improve their English speaking ability by listening to everything on English-speaking radio programs.

“I learned English at school, but all I could say eight years later was ‘London is the capital of Great Britain,’” recalls Fyodor, 69. “To make up for lost time, I listened to the BBC. My parents’ summer residence was about 25km from the capital, and the radio signal there was better than in Moscow (there was no jamming to destroy “enemy radio” like in the capital). When I first listened to the BBC, I couldn’t understand a word. Six months later, I began to understand it. Listening to the live broadcast eventually helped me develop my language skills.”

Learn English through listening to Beatles music

Radio was not the only source of learning English in the Soviet Union. Some learners found that listening to music was also a good way.

“I had no motivation to learn a foreign language because I was pretty sure I would never go abroad,” recalls Sergei, 56. “My mother worked in publishing and had learned English in the 1940s, but never practiced it. The problem was the same: there was no one to communicate with in English. I didn’t want to waste time learning something I couldn’t use in real life. But 1975 was a turning point. I started listening to the Beatles.”

Soviet students studying English as a second language often mistakenly assumed that learning grammar would open all doors for them. In fact, they could barely speak the language. Their English sounded stilted because the only way they had learned the language was through books and technical materials. There was no place to practice real conversation skills. They could not watch (and understand) an English film. Millions of Soviet citizens studied English for years but could not communicate in English./.

.jpeg)