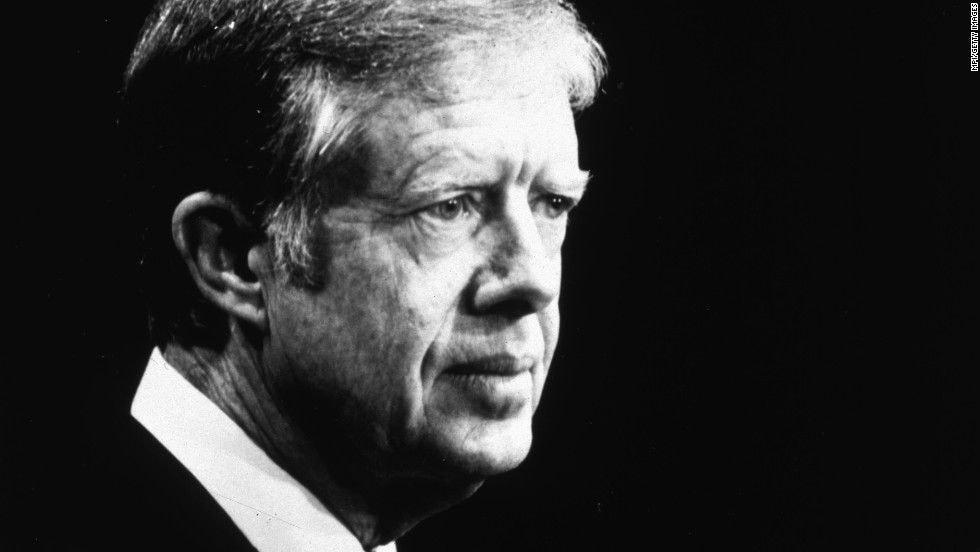

Jimmy Carter and lessons for future generations

(Baonghean) - For Julian Zelizer, a professor of history and public relations at the prestigious Princeton University, there is one memory that has not faded in his mind. It is the image of a 9-year-old boy sitting upright in class when the teacher stopped the lesson so everyone could watch a special event.

They stared at the color television on the trolley, and then saw US President Jimmy Carter standing next to Israeli Prime Minister Menachem Begin and Egyptian President Anwar Sadat to sign the historic peace treaty, the first real diplomatic breakthrough in the Middle East.

|

| Jimmy Carter, the 39th President of the United States, served from 1977 to 1981. |

That day26/3/1979. Professor Zelizer still remembers the tears flowing from the eyes of his teacher. All the students present applauded. And that moment was his first clear political memory.

It is remarkable that more than 30 years later, the Camp David Peace Accords are still in effect. The popular memory of Carter may be of his failures on many issues, but this diplomatic achievement remains a remarkable moment of presidential leadership in international relations – a model for future presidents as they seek to pursue peace in this troubled region.

Sadat made a bold move that shook the region’s war-torn status quo. In November 1977, the Egyptian president made a historic visit to the Knesset, Israel’s legislature. The reasons for his surprise visit were complex, ranging from a genuine desire for peace, his own battles with the Muslim Brotherhood, and Egypt’s weakened economy due to declining Soviet support.

Sadat appealed for peace, telling the Knesset in Arabic: “If you want to live with us in this area, I tell you frankly that we welcome you in security and safety.” Begin, the leader of the hardline Likud party, who had just become Israel’s prime minister, was impressed and decided to enter negotiations. “We Jews know how to appreciate such courage,” Begin said.

Carter seized the opportunity. The months that followed were not easy. In March 1978, the Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO) launched a horrific attack—entering Israel via the beaches near Tel Aviv, traveling in zodiac boats—and killing 38 Israelis, including 13 children. Begin angrily declared to the Knesset: “Gone forever are the days when Jewish blood will be shed without punishment.” Israel responded with a bombing campaign against PLO posts in Lebanon, killing thousands.

In an effort to make progress, Carter invited Begin and Sadat to meet at Camp David from September 5 to 17. In his memoir, Carter said his wife, First Lady Rosalynn Carter, suggested it as an “ideal location.”

Each leader came to the negotiating table with considerable psychological preparation. Many have argued that Carter’s ability to facilitate negotiations represented one of his strongest moments. He opened meetings by telling participants that if discussions failed, “I will announce my final proposal and let each person explain why he accepts or rejects it.”

The meetings were held in secret, with staff strictly limiting media access and trying to prevent leaks. The negotiations were tense. Carter, clearly more sympathetic to Sadat than Begin, acted as a go-between. After three days of no progress, the US president separated the two leaders to try to find common ground.

Carter insisted on a comprehensive peace plan for the region that included disputed territory between Egypt and Israel as well as a territorial agreement in the West Bank.

The US president thought peace with the Palestinians was essential to broader peace in the region. But as negotiations progressed, he realized that reaching an agreement on the Sinai Peninsula was the best path to agreement, and accepted leaving the Palestinian issue unanswered.

Sadat was unhappy because he considered this essential, and was concerned about the political consequences of not including it in the package.

As the negotiations neared their conclusion, the situation appeared bleak, and Carter criticized both men. He told Sadat that failure to reach an agreement would irreparably damage US-Egyptian relations and their personal friendship.

In a crucial exchange, Carter met Begin, who was angry with the American President and blamed the meetings for being leaked. Carter, not optimistic about reaching an agreement, decided to bring the eight signed photos that Begin had previously requested to his nephew. When Carter showed the photos, Begin was deeply moved. He began calling each of his nephews by name and finally urged the American President to try one last time.

Carter's lobbying paid off. The 13-day talks produced the "Framework Agreement for Peace in the Middle East," which outlined goals including Israeli withdrawal from the Sinai and Egyptian recognition of Israel. It left the West Bank unanswered.

Although polls showed a dramatic increase in Carter’s approval ratings, his adviser Hamilton Jordan almost exaggerated these political gains, boasting that the US had “completed the hardest part of wooing Israel.” Negotiations then slowed down. The Knesset approved the peace plan, but Begin also authorized the construction of more Israeli settlements in the West Bank, further inflaming the situation.

Carter is often remembered for his political ineffectiveness, but in this case his administration undertook a major campaign to win the support of the Jewish community. He held regular meetings with Jewish religious leaders and organizations, even appearing in synagogues wearing Jewish hats to assure the community that the agreement would be safe for Israel.

The tense negotiations ended with a breakthrough. Egypt and Israel accepted the deal. Israel would withdraw its troops from the Sinai, and Egypt would recognize Israel and begin diplomatic talks. The issue of Jewish settlements and the West Bank was put on hold. Both countries were guaranteed financial support from the United States, and Israel would receive help with oil supplies if Egypt stopped supplying them.

The historic handshake between Sadat and Begin in front of the White House on March 26 of that year was an iconic moment. When Begin arrived, he said: “This is the day we have been waiting for, let us enjoy this day.”

All three radio stations reported the event live. In Jerusalem and Tel Aviv, the streets were filled with jubilation. Sitting between the two leaders at the signing, Carter told reporters that prayers for an agreement “have been answered beyond all expectations.”

“The signing ceremony was well attended, very enthusiastic and relaxed,” Carter recalled in his memoir. “Sadat praised me profusely; there was no mention of Begin at all. Begin made a longer speech. All of it was enough to show the historic importance of the treaty. I only pray that we will maintain the spirit of cooperation in the future.”

The agreement was not a complete success. A bomb exploded in central Jerusalem the day after the agreement was signed, killing one person and injuring 14 others, leaving many in the United States skeptical about the agreement’s survival. Carter’s political struggles with a second oil embargo in the summer of 1979 sent his approval ratings plummeting, erasing any memory of his success.

Ronald Reagan defeated him in 1980. Rather than recalling Carter's diplomatic breakthrough with Israel, voters seemed more influenced by Republican accusations that Carter and the Democrats had failed to lead the country—with the Iran hostage crisis and the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan occurring during his tenure.

But during his brief time in office, Carter was victorious with a treaty that outlived his presidency.

As policymakers seek to repeat this, with Iran, with Israel, and with many other countries in the region, they should look back at this one-term president to see how he managed to do what no one has achieved since.

Thu Giang

(According to CNN)

.png)