Comrade Hoang Van Tam - Soviet soldier who maintained revolutionary spirit

Faced with enemy torture, comrade Hoang Van Tam (1910 - 1932) was not shaken, but also encouraged the green-clad soldiers to clearly see the revolutionary situation... He died when he was only 22 years old.

Hoang Van Tam's hometown was in Van Loc, a small village located on Cua Lo beach, Nghi Loc district (now Nghi Tan ward, Cua Lo town), Nghe An province. His father, Mr. Diem, was a poor but very outspoken Confucian scholar. Unable to bear the oppression of the village's local officials and tyrants, he left Van Loc to go to the mountains to work as a lumberjack.

Hoang Van Tam was born in Ke Bang (Quy Chau). Growing up in the middle of the vast mountains and forests, under the education and training of his upright father, Hoang Van Tam carries within him the blood of indomitable and resilient people.

His father died, Tam followed his mother back to the countryside. Not long after his mother died, Tam left the village again. From Ke Bang to Vinh - Ben Thuy, Hung Nguyen and then to Nghi Loc... Hoang Van Tam went to many places, studied and did all kinds of jobs: cutting hair, sewing machines, repairing bicycles, carrying water for hire...

It was the days of wandering here and there that helped Hoang Van Tam learn more. By traveling with fellow workers, contacting progressive intellectuals, meeting Tan Viet party members, Tam understood what oppression and exploitation were, what patriotism and freedom were, why one had to rise up and fight for rights... The light of revolution broadened the eyes of the poor young man, showing him a new path.

In 1928, Hoang Van Tam began participating in the Tan Viet Party right in his homeland. At that time, the revolutionary base in Nghi Loc district was still very thin. The whole district had only 8 or 9 people, they often met together, studied progressive books and newspapers of Huynh Thuc Khang, Ngo Duc Ke... They attended political training classes, passed on revolutionary poems to each other by word of mouth...

Hoang Van Tam was assigned by the organization to meet, talk, and organize youth in the Thuong Xa area. At that time, Hoang Van Tam opened a tailor shop right in Van Loc village. He used this tailor shop as a contact point for Tan Viet party members. Day after day, the village boys often gathered here to play and chat. Some of the customers were Van Loc people, but there were also many people from other villages. They came here not only to sew. The torn pants, shirts, and pieces of cloth they carried were just an excuse to meet Hoang Van Tam.

Mr. Tam came to them through many ways. His optimistic life, love of life, modesty, simplicity, especially his broad knowledge had a strong attraction to the young people in the village. He did not like drinking or gambling and often advised his friends to stay away from those dangerous traps. Meeting the young people in the village, Hoang Van Tam often told them about the examples of chivalry of the ancestors in history books or taught them new songs, songs that evoked national pride in the youth of Van Loc:

Being a man, I travel all over the world.

How not to be ashamed before the mirror of Lac Hong

The life of Van Loc youth gradually changed, becoming happier and healthier. Van Loc people loved Hoang Van Tam like their own flesh and blood. People trusted him, listened to his discussions and instructions. People loved and protected him while he worked right under the enemy's guns. Thanks to knowing how to rely on the working masses, no matter how difficult it was, Hoang Van Tam always completed the tasks assigned by the organization.

In early 1930, Hoang Van Tam joined the Communist Party of Vietnam and was appointed by his superiors to the Nghi Loc Provisional District Party Committee, in charge of printing. Hoang Van Tam alone was responsible for writing, printing, and distributing documents. To hide from the enemy, Hoang Van Tam chose to set up a printing office right in the Hoang family church. Every day, in the dim light coming through the crack in the door, Hoang Van Tam worked tirelessly. His already white skin became even paler due to the lack of sunlight. The name "Bach Lap" (White Candle) that his comrades gave him was from that time. Every day, from Tam's hands, bundles and loads of documents and leaflets followed the "dét tê" (traffic) comrades to the villages and hamlets, bringing the Party's voice to the working masses...

Sensing Hoang Van Tam's activities, the Van Loc gang spies were watching him closely, following his every move. The District Party Committee decided to move the printing office to the house of Mr. Tuoc, a new comrade assigned to work with Hoang Van Tam in printing. In a small house discreetly covered by torn mats and thin cloth, Party leaflets and documents continued to be printed right under the enemy's guns.

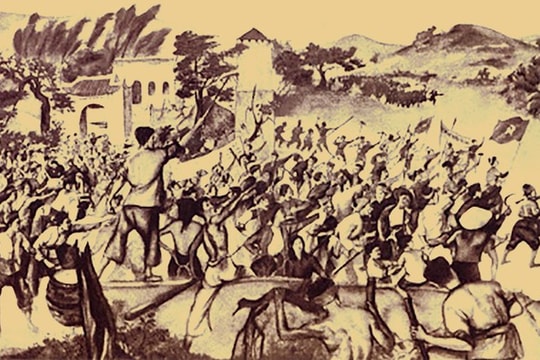

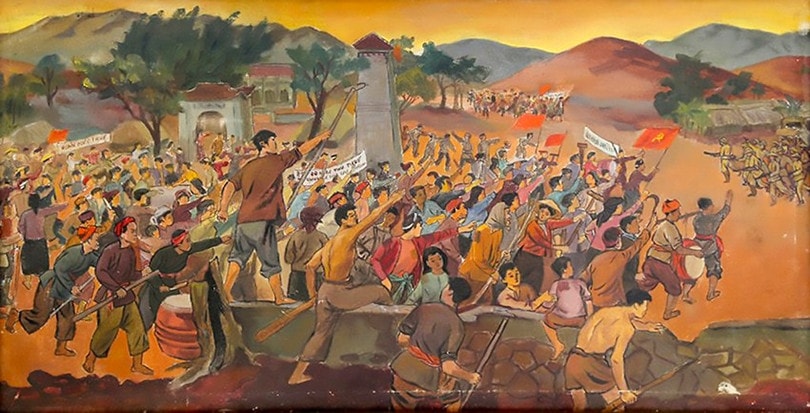

In the fall of 1930, along with the people of the whole province, the people of Nghi Loc lived exciting days. Many protests against high taxes and duties broke out throughout the district. Leaflets appeared like butterflies. The movement was on the rise, Hoang Van Tam and his comrades worked enthusiastically day and night. He also took advantage of time with his comrades to meet with the people and give propaganda speeches.

On September 28, 1930, farmers from all over Nghi Loc district demonstrated and marched down to Cua Lo to free their imprisoned comrades. The enemy, entrenched in the fort, opened fire, injuring and killing many people. The protesters remained in close formation, maintained their momentum, and continued to advance. The enemy intensified their suppression and search everywhere. Hoang Van Tam was on the list of wanted people. The Regional Party Committee decided to arrange for Tam and several other comrades to escape.

At the end of September 1930, Hoang Van Tam said goodbye to his comrades in Nghi Loc District Party Committee, said goodbye to the people of Van Loc to work at the printing office of Nghe An Provincial Party Committee. Here, Hoang Van Tam printed the Party's "Political Platform" (drafted by comrade Tran Phu) using rudimentary printing methods to distribute to the communes. The letters were large, the paper was bad, the printed "Thesis" was bound quite thickly, not very beautiful, but when writing and printing this important document, Hoang Van Tam put all his heart and soul into every stroke to successfully complete the task assigned by the Party.

Recently, because the enemy had surrounded the agency so tightly, the economic life of the agency was very difficult and deprived. Many days, the comrades had to eat rice with salt or sometimes had to go hungry. But Tam never complained. He still sang, still joked, still debated, still studied and worked enthusiastically. In addition to his main duties, Tam also oversaw all other tasks in the agency. He worried about everything from the meal of the healthy to the bowl of medicine and bowl of porridge when a comrade was sick. He worried about hiding documents carefully, in case the enemy surrounded and raided. When the situation was tense and the enemy searched intensely, Hoang Van Tam still stayed up all night to guard the agency so that his comrades could sleep peacefully.

For Hoang Van Tam, Party documents are more precious than the life of a Party member. In the printing agency, each piece of stone, each sheet of paper is the blood and bones of the masses, and it is not easy for the Party to buy them all at once. Tam often recounts the image of Comrade Tuoc before his sacrifice to his friends and reminds everyone: "We can be captured and sacrificed, but we cannot let Party documents fall into the hands of the enemy."

One time, Hoang Van Tam and some traffic officers went to Dien Chau to open a training class on how to print stencils by hand for local printing officers. When they arrived at Dinh market (Yen Thanh), he was surrounded by district soldiers. Taking advantage of the chaos, Tam kicked the team leader to fall into the field and ran into the market. The soldiers panicked and picked up their guns to chase after them. They shouted loudly and shot randomly into the air, but the people pushed each other to try to stop them.

Hoang Van Tam ran around the market and mixed with the crowd to escape. But he did not want to escape alone, but calmly returned to the old road to pick up the traffic comrade and find another way to safely reach Dien Chau.

In early March 1931, the Regional Party Committee decided to transfer Hoang Van Tam to strengthen the Nghi Loc district movement. He happily returned to his hometown, working with his comrades and relatives to build the movement.

Just arriving in Nghi Loc, on June 26, 1931, Hoang Van Tam was invited to attend the expanded conference of the District Party Committee to discuss strengthening the movement. He and a number of other comrades brought incense and gold, pretending to be people attending the death anniversary, and went to Xuan Dinh (now in Nghi Thach commune) to attend the meeting.

Due to a traitor's tip-off, Tran Mau Trinh, Nghi Loc district chief, along with the Tay garrison of Xam market, personally commanded 100 soldiers in green uniforms and a group of porters to surround Xuan Dinh village. The delegates attending the meeting saw the commotion and tried to find a way to escape. Hoang Van Tam jumped down and hid under a nearby well. A moment later, he slowly emerged from the well to listen to the situation. Unexpectedly, a soldier saw his head. He quickly rushed back to the well and shouted loudly. Knowing that he had been exposed, Hoang Van Tam jumped onto the edge of the well to find a way to escape. The soldiers and porters rushed to arrest him, he struggled to resist. But because of that, he was caught in the net!

However, Hoang Van Tam still calmly persuaded the soldiers and the porters: "We made the revolution to overthrow the imperialists and the Southern Dynasty, to overthrow the bloodsuckers of the people. You were also exploited, oppressed, and ridden over, your wives and children were also hungry and miserable, with no food to eat or clothes to wear. You should have supported the revolution, why did you follow them and arrest us?"

Hoang Van Tam's dignified and dignified attitude surprised the soldiers, who stood there listening. District Chief Tran Mau Trinh rushed in and slapped Hoang Van Tam hard on the mouth. He dodged to avoid the slap, but continued to speak. Angry and scared, Trinh raged like a mad dog. He pulled out his gun and shot Tam in the leg. Hoang Van Tam fell down, still shouting: "Down with terrorism, down with Tran Mau Trinh".

His hateful screams affected the morale of the soldiers and the porters. Tran Mau Trinh turned pale and left. Hoang Van Tam continued to propagate the revolution. He exposed the true face of imperialism and feudalism, and exposed the traitorous lackey Tran Mau Trinh. The soldiers listened to him. Trinh was frightened when he saw this, and quickly sent the soldiers and porters to search the bamboo bushes of the village.

The sun was almost at its zenith, Tran Mau Trinh ordered the soldiers to lead everyone back to the district, but Hoang Van Tam refused to go. Afraid that something would happen if things got messy, Tran Mau Trinh ordered the soldiers to put him on his hammock with a roof and carry him away. Along the way, Hoang Van Tam calmly talked to the soldiers carrying him.

When he arrived at Nghi Loc district office, Trinh brought out the Party traitors to identify him. Seeing their faces, Hoang Van Tam glared and gritted his teeth as if he wanted to swallow those beast-hearted people alive. The traitors cowered like owls in front of the sunlight.

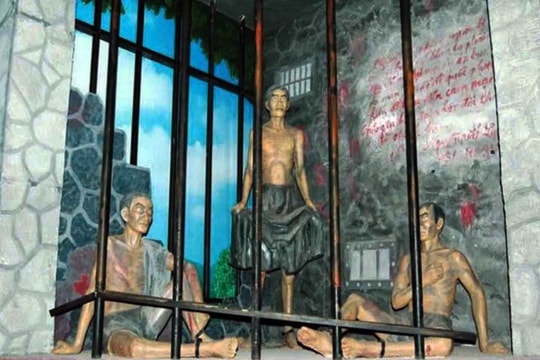

Tran Mau Trinh used dangerous tricks to torture Hoang Van Tam. He used whatever he could get his hands on to beat him. He beat him tirelessly, not caring whether the prisoner lived or died. During the day, they beat him to pieces, and at night, they took him to Vinh Prison for electric shock. His body was bruised like a jackfruit, his clothes were torn and stuck to his bloody body. Every time the comrades in Vinh Prison picked him up, they couldn't take off all the pieces of cloth on his body to massage him.

But no matter how brutally tortured, Hoang Van Tam still maintained his communist integrity. He did not utter a single cry, not a single groan. Amidst the sound of the whip, Hoang Van Tam could still be heard loudly denouncing the enemy, speaking until his voice was hoarse, until the enemy beat him to death.

After nearly two months of torture and using all kinds of savage methods, the butchers still could not subdue the spirit of the young communist. From the district chief Tran Mau Trinh, the French gangs at Xam market, Khanh Due, Song Loc to the French secret police chiefs in Vinh such as Humbert, Bi De... they could not get a confession out of him as they wanted.

Once, Tran Mau Trinh questioned him:

- Who taught you to make revolution?

Hoang Van Tam answered loudly:

- No need for anyone to show, if you are oppressed then you must make a revolution.

He said:- You guys try to imitate Soviet communism, but you can only do it... Hoang Van Tam said straight to Tran Mau Trinh's face:

- The Indochina Revolution will definitely win. And not just the Indochina Revolution. All nations will rise up to destroy you all.

Unable to do anything to him, he was thrown into prison. Hoang Van Tam limped along the rough walls, talking to each of his imprisoned comrades. His friendly, passionate voice encouraged many of his comrades to keep their spirits up.

The enemy was frightened and handcuffed him alone in the barracks. Hoang Van Tam sat there, his hands tied behind his back, his body emaciated, his limbs like reeds, his wounds from long-time untreated were getting more and more painful. But he still took advantage of the opportunity to spread enlightenment to the soldiers.

Day by day, Hoang Van Tam's reasonable and emotional words gradually permeated the soldiers. Many people thought about the courage of the young political prisoner. Some people admired his will, and after hearing his right words, they loosened their grip and stopped beating him as savagely as before. Some people occasionally even secretly gave him gifts. The village chiefs and gang leaders who witnessed Hoang Van Tam's torture also had to shake their heads and stick out their tongues:

-Wow, what a brave person! Truly a man of steel!

Hoang Van Tam's indomitable example resounded throughout the district, touching people's hearts. His fellow prisoners in Nghi Loc prison wrote poems praising him:

Nghi Loc, Hoang Tam is so good!

Compared to courage, who can compare?

Many times of torture, the heart does not change

Loyal and unwavering

Propaganda in front of the terrifying enemy

Speech to the drunken soldiers

Courage is unmatched

Nghi Loc, Hoang Tam has done well.

Tran Mau Trinh intended to sentence him to death. He wanted to kill him to intimidate the Nghi Loc movement. Knowing the enemy's ambitions, Hoang Van Tam was not shaken in the slightest. He remained calm, still laughed and sang, still chatted happily with his comrades in prison, still gently advised his fellow soldiers, and showed the heroic spirit of a revolutionary soldier. The day Tran Mau Trinh forced Hoang Van Tam to sign the verdict he had fabricated, he proudly took a brush pen and wrote a few lines refuting his unreasonable accusations.

Not long after, Hoang Van Tam was transferred to Vinh Prison. Hoang Van Tam's leg had healed, but he was disabled and had to move around. He was appointed to the prison's representative committee, responsible for communication with the outside. In addition to that task, Tam also actively taught culture to some comrades who studied right on the prison's cement floor.

Despite having difficulty walking, Hoang Van Tam still practiced traditional martial arts with his fellow political prisoners, guided by comrade Chu Trang, member of the Dien Chau District Party Committee. Every day, at dawn, Hoang Van Tam would limp up to review some new martial arts moves. He wrote the novel “Lo Giang - Kiem Son” to encourage his fellow prisoners. The novel tells the story of two young men and women, Lo Giang and Kiem Son, who both joined the revolution. When the movement collapsed, they struggled together to piece it back together. Arrested and tortured to death many times, they still maintained their revolutionary spirit. In prison, they still tried to study and practice so that they could continue their work later...

The Southern government had sentenced him to death and was about to take him to the execution ground. But Hoang Van Tam was not shaken. He still asked comrade Nguyen Duy Trinh, who had just been arrested, about news of the movement, about union work, and about political issues that he did not understand.

He was eager to know more about the situation outside and still dreamed of one day returning to work. In that young communist, the belief in victory in the future was still as strong as in the days of freedom.

On June 19, 1932, the French colonialists and the Southern Dynasty of Nghe An handed Hoang Van Tam over to Tran Mau Trinh to carry out the death sentence. Tran Mau Trinh took Hoang Van Tam to Khanh Due village, next to his village, to execute him. After reading the sentence, Tran Mau Trinh asked Hoang Van Tam:

- Anything else?

Hoang Van Tam stretched his body and looked straight into the enemy's face:

- Want to kill all of you. If I die, thousands and thousands of people will rise up to overthrow you, you will definitely be destroyed. !

Tran Mau Trinh panicked and shouted at the soldiers to stuff a towel and tie his mouth with rope. Hoang Van Tam whipped hard, continuing to expose the enemy. The soldiers hurriedly put a metal bit in his mouth. The guard hastily ordered to shoot. He slowly bent down, but suddenly raised his head. Another explosion followed, Hoang Van Tam collapsed and said goodbye to his compatriots.

People held back their tears as they carried his body back to the foot of Lo Mountain for burial. Many people could not hold back their tears as they had to say goodbye to their dear comrade. One comrade, upon passing by his grave, wrote:

At the grave suddenly remember the old person

Tears of sorrow are still hard to prevent

Nine sacred springs of chivalry

Hatred still lingers after a public grudge has not been avenged.

Hoang Van Tam died heroically at the age of 22, but his example of resilience and courage will live forever with future generations.