Nature – The Big Gap in Special Education

Not everyone knows: for children with developmental disorders, especially autistic children, nature is not just a place to play, but a powerful, sustainable and gentle educational and therapeutic method.

Author: Mai Duong | Publication date: April 8, 2025

In the cramped hallway of an early intervention center, a young mother watches her child run around anxiously. A few meters away, a teacher tries to get another child to sit still and do an assignment. Both – parent and teacher – are striving for the same good, but perhaps... in the wrong space.

Not everyone knows: For children with developmental disorders, especially autistic children, nature is not just a place to play, but a powerful, sustainable and gentle educational and therapeutic method.

.png)

A paradox is happening: when autistic children are young (0–6 years old), many early intervention and support programs are implemented. But when children enter primary school age and beyond, everything seems to… fall apart.

From the age of 6 to under 18, many autistic children are “withdrawn” from the formal school system, but there is no suitable alternative environment. Many parents have to send their children to facilities that only serve the purpose of “safe childcare”, completely lacking in the goal of education or real therapy.

Meanwhile, this age group – from 8 to 16 – is the stage where children begin to develop self-awareness, have a higher need for social interaction, and often face feelings of isolation and insecurity if not properly guided.

.png)

Older autistic children may not like to talk, not cooperate in class, cannot participate in large classes – but many are willing to sit under a tree, attentively watering vegetables, feeding fish, or walking with adults through quiet streets.

Nature is the “universal language” when words become difficult. No need for too much guidance, no need for close supervision – just a safe and familiar space, children can self-regulate, find their own emotional rhythm.

This isn’t a sentimental view. A 2021 study published in Frontiers in Psychology found that adolescents with autism who participated in intervention programs that involved gardening, caring for animals, or engaging in outdoor activities had significantly lower scores on anxiety and self-stimulatory behaviors, especially among those who stopped cooperating in indoor therapy sessions.

.png)

We are used to thinking: learning is learning – living is another matter. But for children with developmental disorders, learning is living properly, forming a regular biological rhythm, clear habits and safe reactions to the world.

An autistic child does not need to learn 20 new words every day, but needs to know how to wake up – eat – work – relax – sleep in a predictable sequence. Nature, with its day and night light, with its regular sounds, with activities related to earth, water, trees, sand… is the ideal space to build these rhythms of life.

When the learning environment has rhythm – children learn.

.png)

Many parents and teachers expect their children to speak, write, and understand commands. But before these advanced skills can emerge, children need to rewire their sensory systems – something that music, rhythm, and movement can do better than any curriculum.

International practice has proven that simple, repetitive songs – when combined with actions (clapping, jumping, walking in circles, washing hands to the rhythm...) – help children form stable reflexes. That is why current integrated intervention programs incorporate music into all activities: from studying, eating, sleeping to group work.

When combining music with open space – children no longer learn only by memory, but also by a sense of security and love.

A good special education teacher is not only a good communicator, but also a person who knows how to observe – how to wait – how to create situations for children to progress on their own. That requires time, space and creativity.

In a closed classroom, teachers are constrained by curriculum, whiteboards, and controlled behaviors. But in the natural environment, teachers have more material to “design experiences”: from a watering session, a raking session, to moments of silent walking with children.

It's a real classroom, no podium – but full of learning opportunities.

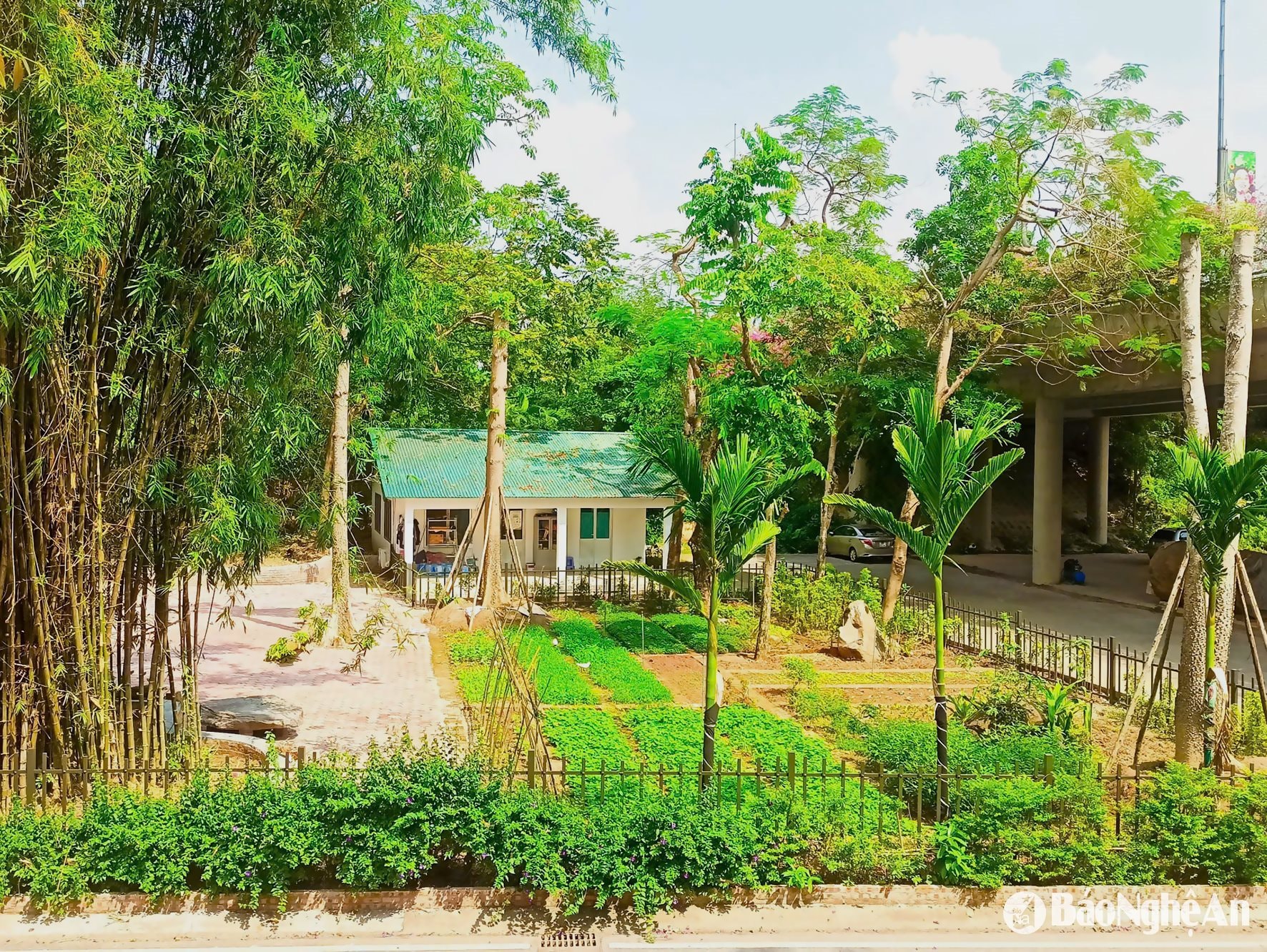

If each special education center is planned with a small garden, a lawn or a vegetable garden, the nature-integrated education model will no longer be the privilege of places with the conditions.

Rules are set, but children are not all the same. Allow some “flexibility” to allow specific models to operate in ways that are appropriate for children – as long as they are safe, have clear goals, and are professionally supervised.

Special education cannot remain a “hands-off” issue. It needs a national strategy, starting with policy – and nurtured by trust.

We may differ in our views, our methods, even our circumstances. But if we look at the child – not as a “difficult case”, but as a life growing every day – all those differences disappear.

Children don’t need a complicated program. They just need a place where they can live at their own pace. And sometimes, that place can start with just a vegetable patch, a banana tree, or a bird singing outside of school hours.

If someone asks, “Where should special education begin?”, perhaps we should answer:

“From the recognition: children with special needs also have the right to learn in nature – like any other child".