The fighting spirit of Nghe Tinh political prisoners at Buon Ma Thuot prison

Communist soldiers in Nghe Tinh homeland, no matter in what circumstances, whether in fighting or being imprisoned and tortured, always uphold their bravery and maintain the steadfast spirit of communists. The nature and character of Nghe Tinh people in the more difficult and harsh the environment, the more they shine and rise strongly. The fighting spirit of Nghe Tinh political prisoners imprisoned in Buon Ma Thuot prison from 1930 to 1945 has proven that.

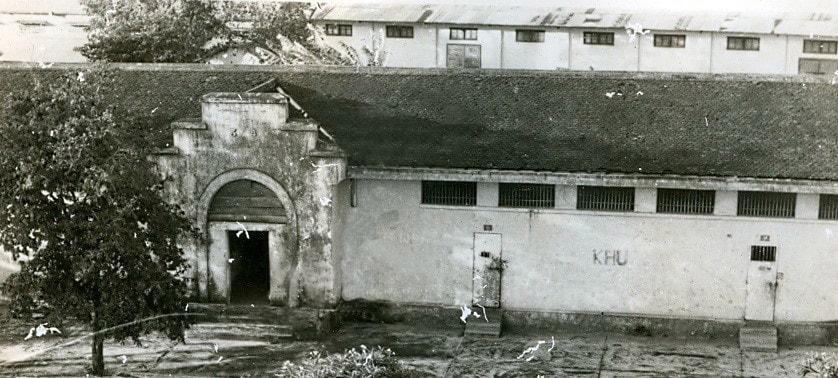

1. Buon Ma Thuot Prison - hell on earth in the middle of the Central Highlands

As early as 1930, when the Nghe Tinh Soviet movement broke out strongly in Central Vietnam, the Resident of Central Vietnam ordered the Resident of Dak Lak to build a prison capable of initially holding 200 prisoners and later up to 600 prisoners brought in from the delta provinces and Central provinces.

By the end of November 1931, the construction of a solid prison was completed. The prison cells were all built with brick walls and tiled roofs. There were 6 prison cells in total, enclosing a yard of more than 1 hectare. A high brick wall surrounded the prison area instead of the shabby bamboo fence and barbed wire. Compared to the prisons of Con Dao, Lao Bao, and Son La - places with solid concrete prison systems with a series of iron gates, Buon Ma Thuot prison was not as solid, but the detention methods and prison regime were no less brutal than other prisons.

Here, the Resident of Central Vietnam personally issued regulations and assigned the Dak Lak provincial government to directly manage the prison guards appointed by the Resident. The task of managing the prison was in charge of the security guards, the prison guards were selected from among the officers in the security force to look after the prisoners according to the regime and military methods. In Buon Ma Thuot at that time, there was a team of green-clothed soldiers of the Montagnards (Ede) commanded by Inspector Maulini and two assistant officers, the chief guard Moshin and Bonelli, who commanded the green-clothed soldiers station of the town and also the warden of the provincial prison. Towards the prisoners of Buon Ma Thuot prison, all three commanders mentioned above were very cruel, especially Moshin. He brutally beat the prisoners and local soldiers, even used bayonets to stab the prisoners and then licked the blood off the bayonets...

When the French colonialists suppressed the Nghe Tinh Soviet movement, a series of cadres, soldiers, and party members were arrested and given heavy sentences. Among them, prisoners sentenced to 9 years or more, or life imprisonment, were sent to exile camps in the Central Highlands in order to gradually kill communist soldiers. In the group of 61 prisoners from Nghe An province sent to Buon Ma Thuot in August 1931, there were 16 people sentenced to life imprisonment, 36 people from 9-13 years. The group of 70 people from Ha Tinh and other provinces were also political prisoners with heavy sentences, classified as dangerous prisoners. That proved the decision of the colonial and feudal government in Central Vietnam was"reserve the Central Highlands to detain the most dangerous prisoners""(1).

Not only that, in Buon Ma Thuot prison, any prisoner who participated in the struggle was punished with an increased sentence. Anh Sang newspaper reported on April 8, 1935:“Recently, at Buon Ma Thuot Prison, three political prisoners, Nguyen Huu Tuan, Nguyen Duy Trinh and Ho Thiet, each had their prison sentences increased by 5 years just because they requested to abolish the punishment of being locked in a cell and eating dry rice every month… Following that incident, another prisoner named Thai Dong requested to widen his leg shackles. As a result, this prisoner’s prison sentence was increased by 5.5 years, but the holes in the leg shackles were still not widened at all.”(2).A prisoner who wrote an article and sent it to the outside world was sentenced to an additional five years in prison. According to the Decree of December 1, 1931 of the Resident of Central Vietnam, those who led the struggles in prison would be confined in solitary confinement, fed bland food, or exiled to Con Dao. In the cell, the prisoners had their feet shackled and their hands chained to the wooden floor.

Like the hell on earth of Con Dao and other prisons, Buon Ma Thuot prison is a place of exile and detention of prisoners with extremely harsh regimes. Not only being imprisoned, shackled, and brutally beaten, prisoners here also have to do hard labor to build prisons, open strategic roads, build houses, bridges, barracks for the army, and garden and plant trees for the authorities. In addition to exploiting the prisoners' strength for economic purposes, they also aim to torture them both physically and mentally, making prisoners exhausted and lose their will to fight, abandoning their revolutionary ideals.

Therefore, the number of prisoners who died at Buon Ma Thuot prison kept increasing. In 1930, when they decided to build the prison, the French colonialists estimated that at least 10% of the prisoners would die each year; but in 1931, they estimated it to be about 25%. In 1931 and 1932, 100 prisoners died, so in just 5 years, the number of prisoners here would be gone.

2. Resilient, indomitable, maintaining the integrity of a communist

Despite suffering and pain, the Soviet soldiers never gave up their struggle. The desire for freedom to return and contribute to their homeland and country always smoldered, waiting for the opportunity to flare up strongly. The struggles of political prisoners in exile took place from 1930-1931 and were really fierce when groups of communist prisoners from Nghe An, Ha Tinh and some other provinces were exiled to Buon Ma Thuot. The common slogan of the soldiers was that no matter what the circumstances or where they were imprisoned, political prisoners must not lose contact, must unite, help each other, especially the sick...

The first struggle was against beatings and poor diet. After collecting evidence, prisoners fought with the prison guards to arrange for good people to replace the cook. This form of struggle quickly attracted prisoners to participate, initially won and opened the way for many struggles with different forms and goals. Hunger strikes, or in the form of slogans and shouting, appeared more and more in the struggles against beatings combined with economic and political demands.

On March 18, 1932, political prisoners organized a large-scale protest against the brutal beatings of soldiers and the poor diet at the strategic road construction site at Km33. The previous evening, a number of prisoners contacted each other to discuss the anniversary of the Paris Commune (1871) to organize a protest and decided to put forward 3 demands:

- No beatings or imprisonment.

- Must be fed better, cleaner food. Must be given meat once a week.

- Must have medicine, must have soap for bathing.

The next morning, when going to work, the prisoners presented their demands to a commander of the red-scarved soldiers. He beat the prisoners and forced them to present their demands. That same afternoon, the group of prisoners returned from work but no one ate their meal due to the commander's threats or enticements. Unable to face the hunger strike of the political prisoners, they hurried back to the town to report to their superiors and at the same time ordered the soldiers to herd the prisoners into the prison camp and shackle their feet. That day, no prisoner went to work, the soldiers called but no one answered. They had the soldiers surround the entire camp, arrest the comrades suspected of being the mastermind and take them to the town prison. The prisoners at the prison camp on the construction site continued to fight for the settlement of their demands and the release of the comrades who were arrested and imprisoned elsewhere. The struggle lasted 3 days, on the 4th day they had to give in to resolve the demands of the political prisoners.

Every day in contact with the soldiers and the Montagnards, we realized that they were people who were indoctrinated with the mentality of dividing the nation and considering prisoners as enemies. Therefore, in order to enlighten the soldiers in general and reduce their beatings and torture of prisoners in particular, the political prisoners tried to learn the Ede language to communicate and propagandize the Montagnard soldiers. The language barrier between prisoners and soldiers was gradually broken down, some soldiers were moved, and later became revolutionary bases to support and follow the Viet Minh.

Fearing the prisoners’ struggles, the French government sought to deal with them. They transferred some prisoners who were considered leaders of the struggles in Buon Ma Thuot to Lao Bao prison or to Con Dao. However, the comrades always kept in mind: “The enemy can take us wherever they want, but the spirit of the revolutionaries is steadfast and indomitable everywhere.”

At the end of 1932, the Mutual Aid Association was formed at Buon Ma Thuot prison to help poor prisoners without families who were sick; to establish discipline to maintain hygiene and order in prison; to protest against prisoners being beaten by guards; to educate about loyalty to the revolution... Thanks to the Association's secret activities, many prisoners were encouraged, empowered, overcame physical pain, homesickness, and determined to maintain the integrity of communists in the face of the enemy's insidious plots and tricks.

In early 1934, the number of prisoners in Buon Ma Thuot reached 650 people. The exile regime became more cruel and strict. Some prisoners secretly wrote letters to the Resident of Central Vietnam, denouncing the exile regime and providing documents for political prisoners who had been released to live in Hue to write articles in newspapers publicly denouncing the crimes of French colonialism and demanding amnesty for political prisoners.

These struggles had a great effect. On the one hand, they denounced the prison regime to public opinion in the country and spread it to public opinion in France. On the other hand, they helped neutralize the enemy's plot to divide prisoners with high cultural level from prisoners with low cultural level; making the solidarity among comrades even closer.

In early September 1934, upon hearing that the Governor General of Indochina, Robanh, and a number of French officials and journalists were coming to inspect the prison, the political prisoners discussed writing a petition denouncing the harsh prison regime. When the inspection team arrived, a comrade stepped forward, handed over the petition, and said in French:“Your prison regime here is very cruel. The jailers have used all kinds of savage methods to beat and kill us. Many of us have been disabled. There is not a single bit of freedom or democracy here, yet you always praise the freedom, equality, and brotherhood of Dafa. I only wrote an article and was sentenced to another 5 years in prison. Where is the freedom then?”(3).

The prisoners' collective presented Governor Robain with a list of 12 demands, including many new points such as the demand to implement the political prisoner regime; demand that political prisoners be allowed to read books and newspapers and not have to do hard labor; demand to improve the diet; demand to abolish the punishment of confinement in cells, eating bland rice, and removing shackles during the day; demand to transfer paralyzed and seriously ill people to the delta provinces; and to transfer prison warden Mosin to another place.

In front of journalists, Governor Robain had to accept the prisoner's demands and transfer Mosin to another place to appease public opinion and prisoners' discontent.

The things seen and heard from Buon Ma Thuot prison were reflected by French journalist André Violit in her book.Indochina calls for helpis a reportage about the repression and terror of the French government in Indochina against the revolutionary movement in the early 1930s.

Encouraged by those struggles, as well as by the impact of the revolutionary movement being restored throughout the country, the struggle of political prisoners in Buon Ma Thuot prison grew stronger, making the authorities confused. Thanks to the struggles in the period 1930-1935, experience in organizing forces and methods of struggle in prison was gradually accumulated, and the harsh prison regime also gradually had to change.

During the years 1936-1939, in harmony with the common struggle of the entire Party and people, political prisoners of Nghe Tinh imprisoned at Buon Ma Thuot prison tried their best to promote and consolidate the victories won in the previous period to continue the struggle to demand improvements in prison regimes and the implementation of political prisoner regimes. The struggles continued to win, creating conditions and precedents for the struggles in the period 1940-1945. In those struggles, many exemplary communist soldiers of Nghe Tinh such as: Ho Tung Mau, Nguyen Duy Trinh, Phan Dang Luu, Phan Thai At, Ton Quang Phiet, Ton Gia Chung, Chu Hue, Ngo Duc De, Mai Kinh, Mai Trong Tin... steadfastly maintained the integrity of communists in the face of bayonets and guns of the enemy.

Not only fighting, the comrades also organized systematic study and training in politics, culture, and military so that when released from prison, they could immediately participate in revolutionary activities, become the core of the movement to fight for people's livelihood and democracy, and prepare for the new fight of our entire Party and people with the spirit:

“… Cultivate yourself and train your will to be steadfast

Whenever I hear the Party call, I take off and fly.(4).

Note:

(1) Encrypted telegram dated December 15, 1931 from the Central Region Resident to the French Consul in Nha Trang

(2) History of Buon Ma Thuot Prison 1930-1945, Institute of Party History; 2010; p162

(3) History of Buon Ma Thuot Prison 1930-1945, Institute of Party History; 2010; p. 72

(4) History of Buon Ma Thuot Prison 1930-1945, Institute of Party History; 2010; p163

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)