The Origins of Revolutionary Journalism in Vietnam

The revolutionary press of Vietnam has always been guided by revolutionary theory, namely Marxism-Leninism and Ho Chi Minh Thought. It can be affirmed that Marxism-Leninism and Ho Chi Minh Thought* are one of the roots of the revolutionary press of Vietnam.

|

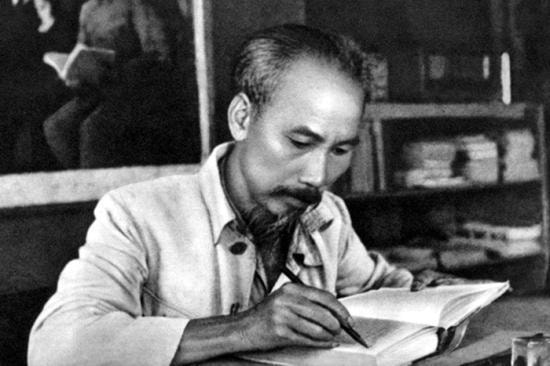

President Ho Chi Minh - The founder of revolutionary journalism in Vietnam. |

The emergence of Vietnamese Revolutionary Journalism - an objective necessity

Entering the 1920s, a new situation emerged in Vietnam. After World War I, the legitimate demands of the Vietnamese people, expressed in the Eight-Point Demands that Nguyen Ai Quoc, on behalf of the Association of Vietnamese Patriots in France, submitted to the Versailles Conference, were not considered by the victorious nations. Furthermore, the French colonialists intensified their efforts to strengthen their administrative apparatus in Vietnam. They enacted policies aimed at exploiting the abundant resources of the colony to serve the mother country's economic recovery and maintain its status as a superpower. "The French Empire promised freedom for the Vietnamese people after the war. But after the war, the colonial shackles tightened even more than before."

Albert Sarraut was sent back to Indochina for a second term as Governor-General. In a speech delivered in Hanoi upon his inauguration, he openly declared "our (French) policy toward the indigenous people" as follows:

"Vietnam is a market for France (…). From France, this land receives the grace of bringing an enlightened civilization that helps it transform: Without that civilization, Vietnam would forever remain in a state of slavery and uncertainty (!). In return, Vietnam will offer France a magnificent pedestal from which France will project the light of civilization further into this part of the earth, and from Vietnam, the influence of France will spread ever wider throughout Asia"… (excerpt: History of Revolutionary Journalism in Vietnam - Assoc. Prof. Dr. Dao Duy Quat, Editor. National Political Publishing House - Hanoi 2013).

Following this policy, the French flocked to Indochina. On the other hand, they also trained a number of native officials, but these officials were only given lower-ranking positions than their white counterparts, received significantly lower salaries than their French colleagues, and were assigned to demeaning positions based on "subordinate ranks," "main ranks," and "Western ranks."

Meanwhile, Vietnamese patriotic and revolutionary movements faced a deadlock in their direction. Comrade Trường Chinh analyzed: "The patriots of the Cần Vương faction advocated expelling the French colonialists but did not abolish the feudal system. Other revolutionary predecessors such as Hoàng Hoa Thám, Nguyễn Thiện Thuật, Phan Bội Châu, etc., also advocated expelling the French colonialists but did not clearly recognize that the target of the Vietnamese revolution was the imperialists, the French colonialists, and the landlord class that had surrendered to imperialism. As for Nguyễn Thái Học and the Vietnam Nationalist Party, they followed Sun Yat-sen's Three Principles of the People, but lacked a practical program to implement in the specific conditions of Vietnam."

Economically, although primarily serving the economy of the mother country, Vietnam's economy after World War I also experienced certain developments. The French colonialists exploited the full potential of our country's agriculture.

Land reclamation in the Mekong Delta was intensified, creating vast rice paddies stretching as far as the eye can see. Noting "a new element in the Vietnamese economy" after World War I, Professor Tran Van Giau wrote: "French capital poured into plantations" and "Colonialists flocked to the red soil of the Central Highlands like cats snatching a piece of fat." Numerous rubber plantations were established wherever conditions permitted. Coffee was widely grown in the North. Coal mining in the Northeast was intensified. Waterways, roads, and railways gradually expanded. Several small mechanical enterprises – mainly repair shops, and some paper, textile, yarn, cement, and processing plants – mostly rice milling for export – sprang up here and there to meet the demands of the situation. According to estimates by American economist Callis, if private investment in Indochina over a period of more than 30 years, from 1888 – immediately after the French established colonial rule in Vietnam – until 1920, was approximately 500 million gold francs, then in just 5 years, from 1924 to 1929, the total investment of French capital reached over 3 billion gold francs. Vietnam's export turnover, from a meager 60 million Indochinese dong in the early years of the 20th century, gradually increased to 230 million dong in 1929. Statistics from the French Labor Inspection Office in Indochina at that time showed that the workforce had grown to over 220,000 people, including 530,000 miners, 86,000 factory workers and commercial officials, and 81,000 plantation workers.

The development of production and the brutal exploitation by colonialism led to the formation of the Vietnamese proletariat. These were the workers in factories, mines, and rubber plantations; alongside them was an ever-increasing number of peasants who had absolutely no means of production, earning a living year-round as hired laborers under extremely difficult conditions. Social contradictions intensified between the colonial rulers and their feudal puppets and the vast majority of the Vietnamese people; between the exploiters and the exploited. The intellectual and middle classes also felt increasingly bitter and hopeless.

However, the patriotism of the Vietnamese people, despite being suppressed, stifled, and exploited through various means, did not diminish but continued to surge powerfully. Through the press and other channels, the echoes of the Russian October Revolution and the struggles of the French people for freedom, democracy, and improved living conditions gradually reached some people, primarily intellectuals and prominent figures. A few French-language newspapers published in Vietnam also contained information – albeit very limited – about the revolutionary situation in Russia and about V.I. Lenin. The time had come for the Vietnamese patriotic and revolutionary movement to need a new direction. Vietnamese society had reached the point where it possessed the minimum necessary conditions to build a vanguard organization to lead the nation on the path of self-liberation, independence, and freedom.

Nguyen Ai Quoc (Ho Chi Minh) became acquainted with Marxism-Leninism in the late 19th century through contact with French socialists. In 1921, with the help of the newly established French Communist Party, he and a number of revolutionaries in French colonies founded the Union of Colonial Peoples to fight against colonialism. After going to the Soviet Union and staying there for a time to study revolutionary theory and practice, in 1924 Nguyen Ai Quoc returned to China to be closer to his homeland and to have better conditions to directly lead the revolution.

Although he had been away from his homeland for over a decade, wherever he went, he always paid close attention to the current situation in his country. He had a good grasp of the activities of the domestic press. In Guangzhou, he maintained close ties with the Tam Tam Society, a revolutionary organization of Vietnamese patriots. In 1925, Nguyen Ai Quoc's book, "The Indictment of the French Colonial Regime," was published in Paris. This book bravely exposed the crimes of French colonialism against our people, causing a stir in French public opinion and having a profound influence in the colonies. That same year, in Vietnam, people in the three regions of the country enthusiastically fought for the French colonialists to pardon the revolutionary Phan Boi Chau, who had just been arrested in China and brought back to Vietnam to be sentenced to death. The speeches of the patriot Phan Chu Trinh were enthusiastically received.

Based on the standpoint of the working class and drawing lessons from the failed attempts of previous revolutionaries, Nguyen Ai Quoc clearly understood that for the Vietnamese revolution to succeed, it had to follow a different path. It had to mobilize and lead the people of Vietnam to rise up, coordinating with the struggle of the French people in France and the struggles of the people of other countries, to overthrow the colonial and imperialist regime and its henchmen, liberate the Vietnamese people from the shackles of slavery, and regain independence and freedom.

But, "without revolutionary theory, there is no revolutionary movement." Without a vanguard organization to lead the revolution along the right path and steps, the revolution cannot succeed. And to launch and rapidly expand the revolutionary movement, to reach consensus on theory, politics, and ideology to build a vanguard revolutionary organization, a revolutionary newspaper is indispensable. "That newspaper – according to Lenin's conception – will be like a part of a giant forge, blowing each spark of class struggle and of the people's indignation into a great fire."

Nguyen Ai Quoc's thinking on journalism coincided with Lenin's views on the role of newspapers in the pre-October Revolution era in Russia. Lenin wrote: "In our opinion, the starting point of activity, the first practical step towards establishing the desired organization, and ultimately the main thread—which, if grasped, will enable us to continuously develop, strengthen, and expand that organization—must be the establishment of an all-Russian political newspaper. We need, first and foremost, a newspaper; without it, it is impossible to systematically carry out a highly principled and comprehensive propaganda campaign."

Like Lenin, Nguyen Ai Quoc understood that having a regularly published newspaper was essential for carrying out propaganda and mobilization work consistently and comprehensively. Nguyen Ai Quoc creatively applied Lenin's idea: "What we absolutely need at this moment is a political newspaper. If the revolutionary party does not unify its influence with the masses through the voice of the press, then the desire to influence them through other, more powerful methods is merely an illusion."

Organizationally, Nguyen Ai Quoc founded the Vietnam Revolutionary Youth Association (Vietnam Revolutionary Youth Comrades Association). As its name suggests, this organization was not yet a Communist Party, but rather a transitional organization leading to the establishment of a Communist Party. The Association served as a breeding ground for enlightenment, training, and education of young workers, farmers, and students recruited from within Vietnam to participate in revolutionary activities abroad. After attending training courses organized by him, these young people would return to Vietnam to engage in revolutionary work. They were the elite seeds of the Vietnamese revolution.

Regarding propaganda, publishing a newspaper was essential. Despite being far from his homeland, Nguyen Ai Quoc was well aware of the state of the press in his country. He understood the difficulties faced by patriotic and passionate journalists. In 1924, in Paris, Nguyen Ai Quoc exclaimed: "In the middle of the 20th century, in a country with 20 million people, there isn't a single newspaper! Can you imagine that? Not a single newspaper in our mother tongue… The French government decided that no newspaper in the Annamese language could be published without the permission of the Governor-General, that they would only allow it on the condition that the manuscript submitted for publication had to be reviewed by the Governor-General first, and that they could revoke the permit at any time. That was the spirit of the decree on the press."

Although abroad, Nguyen Ai Quoc clearly heard the lament of journalists in his homeland: "Having mouths but not being allowed to speak, having thoughts but not being allowed to express them, that is the fate of our 25 million compatriots… For decades, the history of our press has seen journalists completely silenced and deaf… Every time I pick up a pen, pick up a newspaper, I can't help but feel bitter, ashamed, and heartbroken."

It was impossible to publish revolutionary newspapers in Vietnamese domestically. Publishing a newspaper in French would not reach the working class, who were largely uneducated or even illiterate. Having studied the revolutionary experiences of many countries, especially the Russian Revolution, and through his own experience, Nguyen Ai Quoc understood that without escaping the shackles of colonial censorship, he could not openly express his voice, and especially could not loudly denounce colonialism, imperialism, and the feudal clique to awaken his compatriots, as he had done abroad when writing "The Indictment of the French Colonial Regime" and many other outstanding journalistic and literary works that occupied the first three volumes of the complete works of Ho Chi Minh. Through the works of Karl Marx and Lenin, he learned that there was only one way. That way was to organize, edit, and produce a revolutionary newspaper abroad, then secretly bring it back for circulation (and expand it if conditions permitted) domestically.

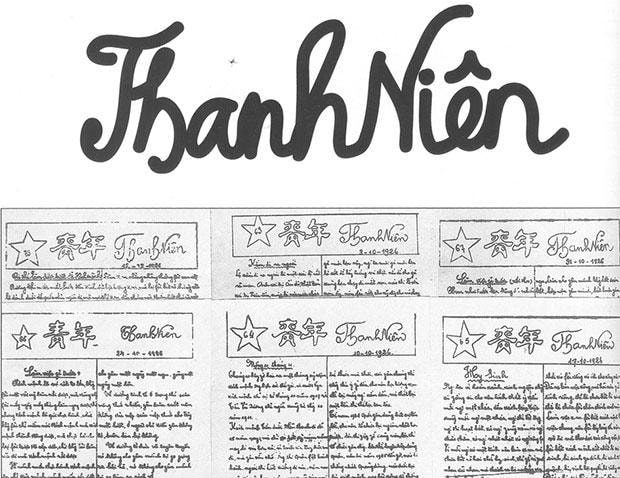

The founding of the Thanh Nien (Youth) newspaper, with its first issue published on June 21, 1925, was a wise and correct decision by Nguyen Ai Quoc. This decision had an enormous impact on the Vietnamese revolutionary process from the mid-1920s onwards. With nearly 90 issues published almost weekly over two years, Thanh Nien accomplished the great task of "illegally circulating within the country and beginning to spread Marxist-Leninist ideology among our people." The work "The Revolutionary Path," primarily based on articles published in Thanh Nien, outlined the roadmap that led our nation to the successful August Revolution and continued to build the glorious achievements we have today.

The Thanh Nien (Youth) newspaper, founded, directed, and edited by Nguyen Ai Quoc (Ho Chi Minh), played a crucial role in preparing the theoretical, political, ideological, and organizational foundations for the establishment of the Communist Party of Vietnam. With the birth of Thanh Nien, a new type of journalism emerged in Vietnamese journalism: revolutionary journalism. This was a very important contribution, a golden milestone in the process of building Vietnamese national culture.

|

The launch of the Thanh Nien newspaper, with its first issue published on June 21, 1925, was a wise and correct decision by Nguyen Ai Quoc. |

Reflecting on our origins

When the first issue of Thanh Nien (Youth) newspaper was published, Vietnamese national-language journalism had already existed for sixty years, beginning with Gia Dinh newspaper. However, if we count from the day K. Marx founded the New Renminbi (June 1, 1848) as the organ of the League of Communists, initiating the revolutionary press movement in the world, then it was 77 years. In the vast Soviet Union, revolutionary journalism had become the press of the ruling party and an integral part of the country's political system.

Ninety-seven years have passed since that day. Vietnamese revolutionary journalism has made tremendous strides. During the period before our people seized power, amidst the brutal repression and harsh colonial rule, revolutionary journalism had to operate illegally, yet it never ceased to develop. While central government newspapers might be confiscated or cease publication because their leaders were arrested, newspapers of regional, provincial, and district committees continued to circulate. After the August Revolution of 1945, each time the revolution reached a decisive turning point, journalism had the opportunity to develop to a new level. Through the ups and downs of the times, Vietnamese revolutionary journalism has always looked straight at its unchanging direction: striving for independence, freedom, and socialism. This explains why Vietnamese revolutionary journalism has always found suitable forms to adapt, survive, and develop.

Entering the new millennium, the Vietnamese people are proud of the achievements that revolutionary journalism has attained over the past 97 years. To fully understand the development process and, especially, to explain the steadfastness and consistency of Vietnamese revolutionary journalism, it is necessary to go back in time to find its origins.

1. The revolutionary press in Vietnam originated primarily from the patriotic and democratic tendencies within the legitimate press, especially from the time when the national-language press moved beyond its nascent stage, heavily reliant on official publications, to gradually become a press system with all the characteristics of a media outlet, such as regular publication, widespread circulation, a stable readership, and a professional team of journalists, etc.

Right in the second Vietnamese-language newspaper to emerge after Gia Dinh Bao in the latter half of the 19th century, Phan Yen, there was a series of articles openly criticizing the French colonial regime's policies. Naturally, the authorities sought to counter, prevent, and suppress these criticisms. However, the patriotic, democratic, and progressive voices reflecting the indomitable will of our people were not silenced; on the contrary, they continued to resonate more clearly and boldly in various forms. The journalistic works of prominent figures such as Diep Van Cuong, Tran Chanh Chieu, Nguyen An Ninh, Phan Van Truong, Tran Huy Lieu, Phan Chu Trinh, Ngo Duc Ke, etc., although published in legal and public newspapers, mostly with the money and patronage of the authorities, carried a strong indictment and resistance against the colonial regime and its feudal henchmen. Promoting patriotism and love for one's people, upholding compassion, maintaining unwavering resolve, encouraging economic revitalization, demanding freedom of business and freedom of the press, calling for the eradication of outdated customs, and denouncing corrupt officials…

2. Within the intrinsic roots – one could call tradition – of Vietnamese revolutionary journalism, a very important source is the patriotic and revolutionary poetry and literature of the late 19th and early 20th centuries. These include the works of Nguyen Dinh Chieu, Nguyen Thong, Doan Huu Trung, Tran Xuan Soan, Phan Dinh Phung, Nguyen Thuong Hien, and others from the latter half of the 19th century. Among these works, many are anonymous but were widely circulated among the people in the form of folk songs, chants, couplets, eulogies, proverbs, and sayings.

At the beginning of the 20th century, the content of journalistic and literary works (mostly circulated outside of legal channels) gradually lost its loyalty to the king according to Confucian principles as in the late 19th century, and leaned towards innovation, advocating for the advancement of public knowledge and demands for civil rights. Examples include Phan Boi Chau's blood letter from overseas; Phan Chu Trinh's song "Awakening the Soul" calling on "talented young people to learn all things civilized"; Ngo Duc Ke's essay on orthodox and heterodox doctrines, criticizing Pham Quynh's views on national subjugation; Dang Nguyen Can's promotion of modern learning; Tran Quy Cap's advice to people in the country to learn the national script; and Do Co Quang's eulogy for the twelve martyrs at Hoang Hoa Cuong… The Dong Kinh Nghia Thuc school published the book "New Civilization and Learning," outlining six major policies: using the national script, revising textbooks, reforming examination methods, encouraging talent, revitalizing technology, and especially speaking very carefully and earnestly about the urgent need to publish newspapers in the national language.

Patriotic and revolutionary journalistic works, poetry, and literature, whether published through mass media or circulated among the people through various channels, are the direct and intrinsic sources of Vietnamese revolutionary journalism. This body of journalism and literature reflects the fine traditions of the Vietnamese nation, where "patriotism is the focal point of all focal points, the value of all values. It is the main ideology, the red thread running through the entire history of the Vietnamese nation." From this, tracing back further, it can be affirmed that revolutionary journalism is deeply rooted in the tradition of patriotism and the essence of Vietnamese culture and civilization.

3. The revolutionary press of Vietnam also originates from the revolutionary, democratic, and progressive press of the world, and is deeply influenced by that press, while always maintaining its strong national character.

The founder of Vietnamese revolutionary journalism, Nguyen Ai Quoc, began his career abroad. His first journalistic and literary works—including some of his best—were produced in France and published in progressive French newspapers and magazines, primarily those sponsored by the Socialist Party (before the French Communist Party was founded) and the French Communist Party; later, they were published in Russian and Chinese newspapers. It can be said that French revolutionary journalism shaped Nguyen Ai Quoc's writing career from a young age. During his theoretical and practical studies in the Soviet Union, Nguyen Ai Quoc focused on studying the experiences of Russian revolutionary journalism. Upon returning to China, he maintained close contact and regularly collaborated with Chinese revolutionary journalism.

Before the Thanh Nien (Youth) newspaper was founded, Nguyen Ai Quoc, along with his foreign friends and comrades in Paris, published the first issue of Le Paria (The Pariah), on April 1, 1922, with a clearly revolutionary content. Le Paria contained many articles addressing the Vietnamese issue. However, the newspaper was published in French abroad and clearly stated in its title as the Forum of Colonial Peoples (soon to be changed to the Forum of the Colonial Proletariat). The Vietnam Hon (Vietnam Soul) newspaper originated from Nguyen Ai Quoc's intention to publish and circulate it among Vietnamese people living in France. However, after he left France, the newspaper was launched with Nguyen The Truyen as editor-in-chief, and over time it failed to maintain its original purpose and principles. Both newspapers should be considered as belonging to the foreign origins of Vietnamese revolutionary journalism.

4. Since its inception, the revolutionary press of Vietnam has gone through many ups and downs alongside the revolutionary movement of our people before the August Revolution, experiencing periods of both intense fervor and temporary lulls. After 1945, conditions were generally more favorable than during the clandestine period, but it could not avoid the direct impact of the times. In all circumstances, it has consistently maintained its revolutionary character to continue its continuous development. Since 1986, when our Party initiated and led the comprehensive national renewal under the socialist orientation, the revolutionary press of Vietnam has received further impetus for comprehensive and strong development. By November 30, 2021, with 816 media outlets, encompassing all types of media and employing 17,161 reporters and editors, the Vietnamese revolutionary press has risen to stand alongside the press of developed countries in the region and around the world.

This success is due to its constant guidance by revolutionary theories, namely Marxism-Leninism and Ho Chi Minh Thought. Based on its political and ideological foundation, as well as an examination of the basic characteristics of revolutionary journalism over the past 97 years, it can be affirmed that Marxism-Leninism is one of the roots of Vietnamese revolutionary journalism.

-------------

*. Ho Chi Minh: Complete Works, Vol. 1, p. 428